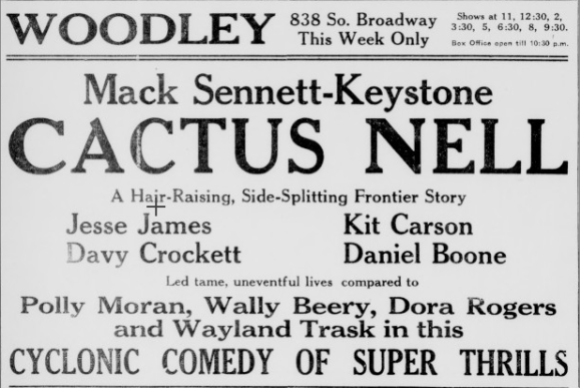

One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported that with the departure of two major producers Triangle Film Corporation was falling apart. Founded in July, 1915, Triangle was intended to be a prestige studio based on productions of D.W. Griffith, Thomas Ince, and Mack Sennett. They succeeded for awhile, with stars like Roscoe Arbuckle, Douglas Fairbanks and William S. Hart, but by mid-1917 they had all left, as had Griffith. Two weeks earlier Thomas Ince had resigned, and on June 30th Kingsley reported that Mack Sennett signed with Paramount Pictures to release all of his future productions. Triangle kept producing films until 1919, but film historian Brent Walker said of their comedies there “was a noticeable drop in quality.”

All of their top talent had gone to where the money was: Paramount and its divisions, Famous Players/Lasky and Artcraft. On July 1st, the company’s vice-president Jesse Lasky announced a very full slate of 27 upcoming films, mostly adaptations from bestselling authors like Mary Roberts Rinehart (Bab’s Burglar) Mark Twain (Tom Sawyer) and Owen Johnson (The Varmint). The company is still around, and is still making films based on familiar properties like Baywatch and Transformers.

Kingsley remarked that comedies were changing, and the subtlest bit of business was no longer the kicking of one gentleman downstairs by another. Her favorite film this week was an example of that, Haunted Pajamas. She wrote:

Speaking of screen comedies, don’t miss that most hilariously funny one of the season, Haunted Pajamas…Harold Lockwood discloses himself as a first rate comedian as the bewildered hero, owner of the bewitched pajamas, the quality of which he does not know, who is certain the whole world has gone mad. If all the magic articles in the Arabian Nights tales had made for as much joy as those pajamas, the Arabs would have laughed themselves to death.

The pink silk nightwear has the power to transform the wearer into someone else; mistaken identity hijinks ensue. The film has been preserved at the Eastman House. Sadly, Harold Lockwood died in the 1918 influenza epidemic.

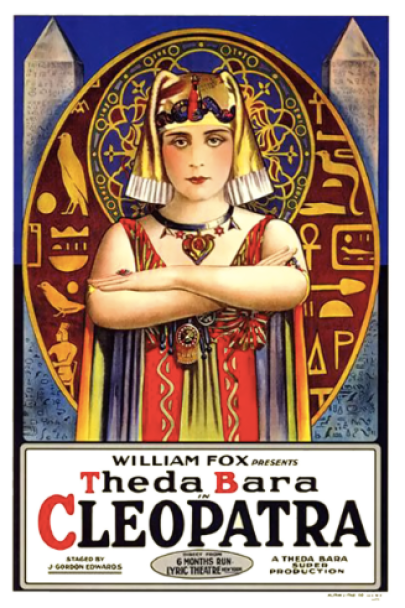

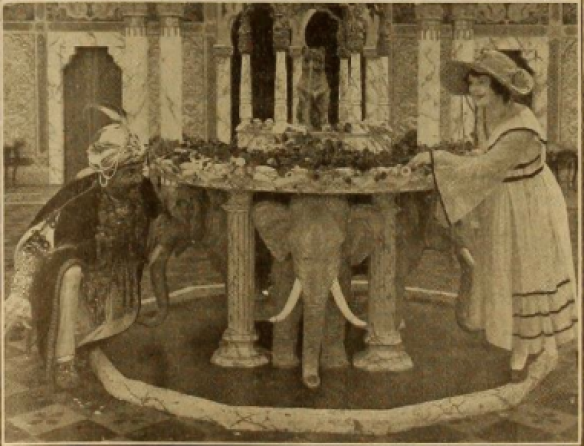

Kingsley got to interview Theda Bara on the set of Cleopatra, and she reported that things were going very well. The production “promises to be the most elaborate and ambitious undertaking of this [Fox] film company. Marvelous sets and costumes are being used.” The weather was hot, and Bara declared that it suited the story, and “she was glad it was not an Alaskan story she was doing.” When asked about her startling costumes, she said “I’ve gotten over being self-conscious in regard to my costumes…And to think, I cried for two days and lost fourteen pounds over having to appear in a one-piece bathing suit in A Fool There Was.” She also talked about how she did her work:

I have the scene thought out in a general way, but upon coming into it, I change many things. This seems due to a sort of inspiration, and especially as a matter of fitting my work to that of others in the scene. Mr. Edwards [J. Gordon, the director] kindly allows me to work out my own ideas. I find it very difficult to work while people are watching me, unless they are in through sympathy.

Kingsley complimented Bara on her poise, dramatic sense and power of concentration, as well as her capacity for hard work.

In an early version of Linda Holmes’ scale of how hot it would need to be before you’d go to an air-conditioned theater to see certain films, Kingsley noted that the cooling system at Miller’s Theater was very good, and Patsy was “a very pleasant little comedy with which to while away an afternoon.“ June Caprice starred as another Mary Pickford-esque tomboy who moves to the big city; it’s a lost film. It would probably be a right around The Karate Kid on the Holmes scale.

While remarking on the great improvement in film music, Kingsley mentioned one young woman’s comment during a film: “Oh dear, I can’t hear what he’s saying. I wish the music wouldn’t play so loud.” She was so absorbed in the story that she’d forgotten it was a silent film. I hope you get to see a movie as good as that this week!