One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley gave us a story that showed that the best trope in fiction can sometimes come true:

When harsh parental edicts thirty-six years ago tore apart two newly-married San Francisco elopers known at the time as Billy Wallace and Georgie Woodthorpe, they did not extinguish but only banked love’s fires, which now have flamed again to reunite Mr. and Mrs. William T. Wallace in a home of happiness in Portland, OR, the two being wed there a few days ago…

Back of the remarriage which took place recently lies the unusual romance of the quickly-thwarted marriage of 1883, the interval of the marriages of the two to others, the rearing of children, and the smoldering of the love that brought the couple together again. During that time Mrs. Woodthorpe-Cooper made a name on the stage, appearing with both [Edwin] Booth and [Lawrence] Barrett.

The romance started when the two were schoolmates. Both ran away from their homes in San Francisco to San Jose, where they were wed, but swift parental interposition prevailed before the marriage was a day old, and finally Mrs. Wallace consented to divorce her young husband.

Aside from a brief meeting seven years ago, they had not seen each other until last February.

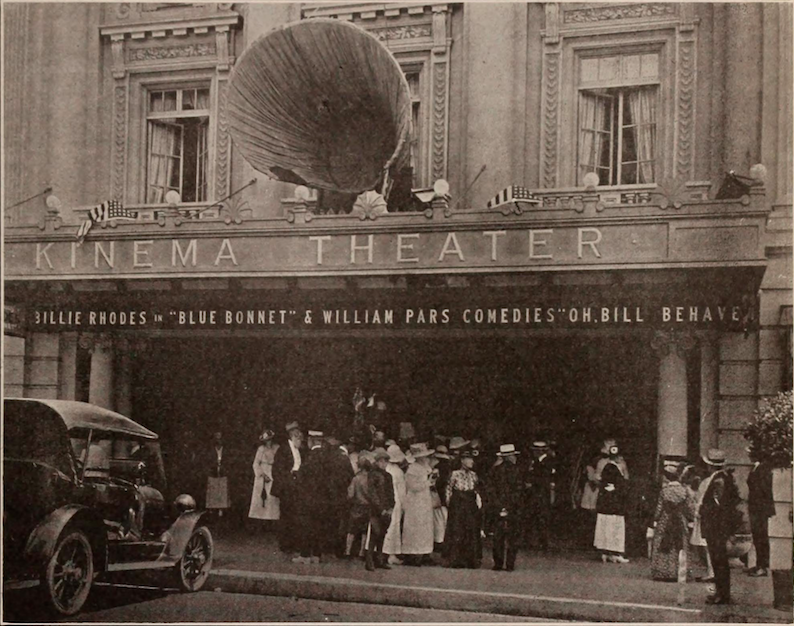

All that’s missing is a “you pierce my soul” letter (hooray for Captain Wentworth!). William Wallace had become a paving contractor in Portland Oregon, while Georgia Woodthorpe married Fred Cooper, a theater manager, and kept acting on the stage. Cooper died in 1912. Woodthorpe had started working in the movies in 1918, and she continued after her third wedding. Her most memorable role was as the lodge keeper’s wife in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921). Mr. and Mrs. Wallace were together until he died in 1926; she died a year later.

However if that early romance hadn’t been thwarted, we wouldn’t have The More The Merrier (1943), which would be awful. The Coopers had three daughters and a son; one daughter, Georgie Cooper, married John Stevens and they had two sons, John and George, who became a film director. He made quite a few other movies that people like at lot, including Swing Time (1937), Gunga Din (1939) and Shane (1953). I’m selfish enough to be glad everything turned out the way it did.

Kingsley’s favorite film this week was Wagon Tracks, a “great desert screen epic.” She enthused:

Never has William S. Hart appeared to such splendid advantage as in this smashing drama of the California desert. In fact, it seems as if all of his former efforts were mere training for this big epic of the outdoors. His vigorous downrightness of characterization, his power to convey deep dramatic feeling, and to impress with a sense of utter sincerity, have never revealed themselves so incisively as against the backdrop of the masterpiece of Mr. [C. Gardner] Sullivan’s—this strikingly original story of the pioneers who faced death in the olden days in order to build our empire in the West.

Hart played Buckskin Hamilton, a wagon train guide, who gets revenge for his brother’s murder. It’s been preserved, and it’s available on DVD.

Kingsley’s least favorite film this week was His Bridal Night, a not-very naughty bedroom farce (“don’t be frightened—they spend the evening in a decorous sitting room”). After the show she overheard:

“It might have been worse!” sighed a fat lady behind me yesterday. “Or better!” responded her escort.

Mr. Chaplin’s publicists were working overtime this week. On Monday Kingsley reported:

Laying aside for the time being his high-brow aspirations to play Hamlet and consenting to be the idol of high-brow, low-brows and no-brows for awhile yet, Charlie Chaplin announced yesterday that today he will commence the making of a new comedy along the lines that have made and kept him famous, and in which, despite his detractors, he is known as a real artist. The theme which Chaplin’s comedy will have is one in which the public is becoming more and more interested, viz. aviation. One scorns, of course, to suggest that an aviation comedy made by Charlie Chaplin will boost Brother Syd’s airplane business!

She’d heard a rumor that it was to be called Sky Jazzing. However, it never got past the tell-the-newspaper-about-it stage, and Chaplin kept working on The Kid. Syd Chaplin did help start the first privately owned domestic American airline, but he got out of the business about a year later, when the government started taxing it and requiring pilots’ licenses.

On Thursday, she ran a sweet story about Reginald Over, a Chaplin superfan who talked his way into the studio by claiming he had a camera innovation. After Chaplin finished shooting his scene and came over, Over immediately confessed that he didn’t, but he said:

“For the past three years I have religiously visited the studios where you have been working; wanted to see you in action. Never got a ‘look in.’ Thought it about time to invent something. So sorry to have troubled you. Mr. Chaplin, many thanks for the entertainment. Good-bye.”

He turned to go, but Charlie invited him to stay for tea.

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find any Reginald Overs living in Los Angeles at the time. But it would be nice if the story were true.

A few weeks ago, we learned that on Monday nights, film people went to the theater. This week Kingsley reported that Tuesday night was fight night for the male part of Hollywood. Professional boxing was illegal in Los Angeles until 1924, so they all trekked to Vernon, a tiny unincorporated town five miles south of downtown L.A. She infiltrated Jack Doyle’s boxing ring there, where she heard “a great roar, the loudest human noise you have ever heard.” The stars she saw did their part to contribute to it:

- “Bryant Washburn, who, you know, always plays the polite, home-broken husband, never misses a Tuesday night. Washburn is always loaded down with cigars when he arrives, because he invariably forgets to take his cigar out of his mouth when he commences to holler—says he never knows when an attack of hollering is coming on—and so drops cigar after cigar to the floor, and has to light another.”

- “Charlie Chaplin forgets he’s a great artist when he arrives at the ringside. He hollers the loudest when he disagrees with the referee, which is nearly always.”

- “Monte Blue puts his hands over his ears when there’s a din—and then hollers his own head off!”

There were a few exceptions, such as Tom Mix. Every Tuesday,“Tom sits as solemnly and quietly as if he were in church.” In addition, Roscoe Arbuckle had the most remarkable reaction to the din: “Fatty goes to sleep—but always wakes up just at the right places!”

Maybe in the coming months, we’ll find out what they did with themselves the rest of the week.