One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley described a quiet work day for Balboa Studios actress, Jackie Saunders:

- Up at 6 o’clock

- Practices on piano until 7 o’clock, then has breakfast and conference with maids and cook.

- Drives to studio.

- Makes up and drives to location.

- Is shot in eight or ten scenes, then back to luncheon at 1 o’clock.

- Drives to Los Angeles, twenty-five miles.

- An hour at the hairdresser’s.

- An hour at the dressmaker’s.

- An hour at the photographer’s.

- A hasty dinner.

- Drives back to the studio (It is now 9 o’clock.)

- Works until 11 o’clock in indoor studio, and is home by midnight.

- Up at 6 o’clock again.

And that’s why unions are so important. Jackie Saunders was married to the studio’s secretary/treasurer, so this schedule probably wasn’t worse than most. She was a theatrical actress who got her start in films in 1911 with small parts at D.W. Griffith’s Biograph Studio, then she moved West to work for Nestor. Balboa hired her in 1914, and she became one of their biggest stars. In her earlier films, she played waifs in need of rescue, but starting in 1917 she moved on to playing either spoiled rich girls or tomboys who got tamed by marriage in the last reel. After Balboa closed in 1918 she worked for Fox, Metro, and Selznick, then retired from acting in 1925.

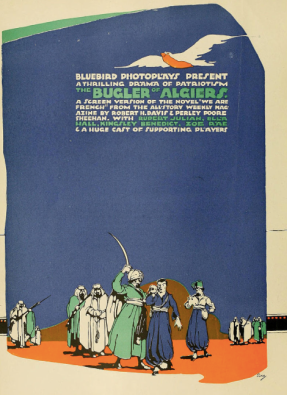

In her reviews this week, Kingsley exclaimed “Oh, for more picture plays like We Are French…Here indeed is film footage worth viewing.” Also known as The Bugler of Algiers she found it a “swift-moving, clean-cut, thrilling drama” and knew of “no film tapestry on view for lo these many moons which is threaded with such colorful incident as this one.” The film was about Anatole and Pierre, two former soldiers searching for Gabrielle, Anatole’s sister and Pierre’s sweetheart, who vanished after her village was ransacked. The film helped make up for another of the week’s releases, The Devil’s Pay Day, a story of a rich man who marries a poor woman and quickly tires of her; Kingsley called it “futile” “improbable” and “claptrap” – “of such we are weary.” Both films are lost.

Kingsley got some practical screenwriting advice from a credible source.

There are more good dramas in the pages of the average newspaper than in anything else I know of,” remarked Jeanie MacPherson, author of Joan, the Woman. “A drama is only a reproduction of human emotions and their reactions, and in no place are the emotions more clearly set forth or at least suggested to the imaginative mind than in their terse phrases of the press. Really I got my first thought for writing Joan the Woman from a story I saw in the newspaper. This story told of the French solders seeing visions of the famous Maid of Orleans over their trenches, inspiring them to deeds of bravery…Dramatists may weave productions out of their own imaginations, but stories of actual life which the newspapers contain every day I believe have a far greater appeal and are far more human.”

Jeanie MacPherson had only been writing scripts since 1913, but she went on to collaborate with Cecil B. DeMille until 1930, co-writing hits like Male and Female (1919) and The Ten Commandments (1923). He particularly valued the ideas she brought, according to a 1957 interview cited on her Women Film Pioneer page.

Kingsley mentioned that James Van Trees Jr., five-year-old son of the cinematographer, offered to trade his family’s new baby for a pair of roller skates. There were no takers. This expert problem-solver went on to become an assistant cameraman. His dad had a remarkable career, lasting from 1915 until 1966 when he shot an episode of My Mother the Car.

Kingsley heard from the Universal lot that there’d been a rash of films being renamed by the New York office, for example, Mary, Keep Your Feet Still became Her Soul’s Inspiration (it was the story of a girl who loved to dance). So Rex Ingram complained that his next picture, The Flower of Doom would be transformed into The Poisoned Bathing Suit. The story of kidnapping and an opium den kept its title and came out on April 16, 1917.

The Buster Keaton countdown continues. On February 1st, Kingsley reported:

To be personally conducted to New York is the honor in store for Roscoe Arbuckle, lately engaged by Joe Schenck as one of his star picture players. For this purpose, avowedly, no less a person than Lou Anger will see that Arbuckle is not kidnapped by any rival firm between here and New York; also that he does not spend all his substance in poker on the train so he has to draw ahead on Mr. Schenck for his salary when he arrives.

If Anger hadn’t gone, there would have been no one to run into Keaton on the street and take him back to Arbuckle’s studio. Most likely, Keaton would have made his way to films eventually, but who knows how long it would have taken.