One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported on a profitable deal:

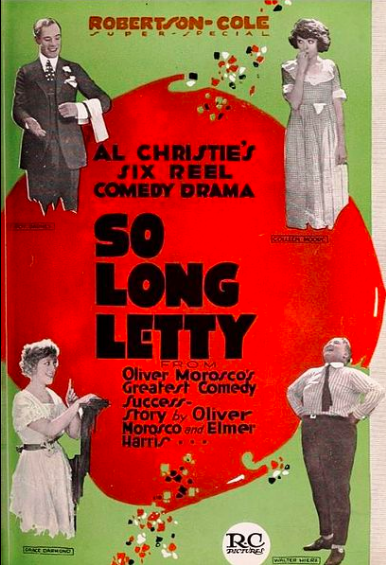

Paying the stated sum of $50,000, the Christie Film Company has just purchased from Elmer Harris and Oliver Morosco the film rights to So Long Letty, one of the most successful musical comedies ever staged in this country, which has been running during the past four years. This is one of the biggest deals put over in the history of picturedom for the purchase of film rights to a play. It is understood that there have been a very large number of offers made to Messrs Harris, author, and Morosco, producer, for the picture rights to this famous musical comedy, but so far, due to the fact that two or three companies have been playing the piece over the country, they have refused to listen to the clink of the picture makers’ money-bags.

The film version of So Long, Letty will be made under the personal direction of Al Christie, and it is expected that the picture will be produced on an elaborate scale, with a featured cast of stage and screen performers.

Charles Christie, co-owner of the Christie Film Company, said it was to be the first of a series of big productions for the company. They hadn’t decided if they’d stop making the short comedies they were famous for (they didn’t, but they did occasionally make more features).

I couldn’t find out if this was actually a record-setting amount of money for film rights. Later articles in the trades put the figure at $40,000. Still, it seems like at lot since the songs were useless in a silent film, and they were left with a plot that sounds like a classic TV sitcom: a homebody wife is married to a husband who loves the nightlife, while their neighbors are a domestic husband and a social butterfly wife, so they trade spouses for a week (as you do). Of course the women recognize this is nonsense and plot behind the men’s backs to make it a miserable experience, and the extroverts are reunited with their introvert spouses. Surprise! But even then, a recognizable title was a valuable selling tool.

Al Christie did direct the film, and it came out just eight months later in October. It got re-made as a talkie in 1929, with its original Broadway star, Charlotte Greenwood.

Usually there wasn’t a dollar amount given when film rights sales were announced. Either the sum didn’t seem newsworthy, or the studios didn’t want to tell. A more typical announcement appeared on the same day: Jesse Lasky bought the rights to Booth Tarkington’s book The Conquest of Canaan, for Paramount/Artcraft, but no other details were given. Paramount did produce the movie; it came out in 1921 and it starred Thomas Meighan. Unlike nowadays, when films rights were purchased the film more often than not got made – probably because the company buying the rights already had the financing to make the movie. Now producers buy options with the hope that they can raise the funding.

In case you were wondering, the current record seems to be the 6 million dollars Sony Pictures paid for the right to The Da Vinci Code.

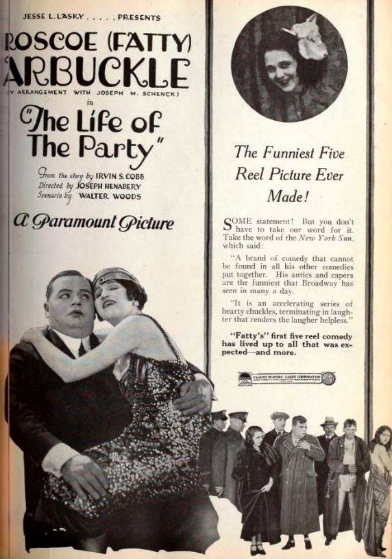

Kingsley’s favorite film this week featured one of her favorite comedians:

I suppose if Dorothy Gish merely recited the alphabet she could do it in a fashion to make us laugh, just as Sarah Bernhardt or somebody is said to have recited it in a manner to make everybody cry, And remember it’s considered easier to make people cry than to make ‘em laugh. And when the dashing Dorothy has a bounding comedy vehicle like Mary Ellen Comes to Town at Clune’s Broadway, well, she’s just going to keep people laughing all the time.

Kingsley admitted that nothing about the film was groundbreaking:

Of course, numberless Mary Ellens of the screen have come to town, and have all been more or less amusing, but it takes Dorothy Gish to ring the bell, furnishing all the little touches of natural comedy that remind us of things that have happened to ourselves. There is a plot, too, with some crooks trying to drag her and the handsome hero, Ralph Graves, into it, but of course, being foiled by Mary Ellen, who hop-skips-jumps out of danger, dragging the hero with her.

She wasn’t the only one who thought it was a fine way to spend an evening, for Clune’s was packed “by a crowd that seemed to relish Miss Gish’s drollery to the limit.” It’s a lost film.

On March 1st, Kingsley reported something that was about to turn into one of the biggest Hollywood gossip stories of the year:

Mary Pickford, it seems, decided after a day or two of resting, that she was pretty well, after all. So she and her mother took a trip to New York. Just what was the object of the trip was, is something of a mystery. One rumor has it that Miss Pickford is contemplating building a studio there.

Mary Pickford was so important that she couldn’t be out of town for a few weeks without people noticing she was away. She was nowhere near New York. She’d been in Minden, Nevada since the middle of February, establishing residency so she could divorce Owen Moore. It was granted on March 2nd. They did their best to keep it quiet, but the secret didn’t last long. On March 4th the LA Times reported that it happened. By March 5th she and her mother were back in Los Angeles and she strenuously denied she was going to marry Douglas Fairbanks. Their wedding was on March 28th, and a long article all about it was in the paper on March 31st.

Of course, it was big news in the fan magazines, too. Here’s Photoplay’s title:

“Mary Pickford Faces Problem,” Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1921.

Otis M. Wiles, “Mary Pickford Denies She’ll Wed Fairbanks,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1920.

“Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks are Secretly Wed Here,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 1920.