One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported that a new film had struck a nerve.

This department is in receipt of several letters from various persons praising in the highest terms [writer] Frank Woods’ picture “The Children Pay” at Clune’s Broadway. The story deals with the sufferings and humiliations suffered by children whose parents are divorced. In fact, the picture seems to have had a wide appeal, not only because of its purpose, which is worked out in a natural and unforced way, but because of the fact that Lillian Gish has several fetching comedy scenes which apparently have caught the public taste.

The Children Pay told the story of Millicent (Lillian Gish) and Jean (Violet Wilky), sisters who have been separated because of their parent’s divorce. To reunite, Millicent marries her lawyer and takes custody of Jean. (Gish was 23 at the time, so it looked less like pedophilia.)

This was unusual because Kingsley rarely mentioned the response she got to her columns. She didn’t entirely disagree with the letter writers; her review said that despite the questionable legality of a minor girl being appointed guardian of her younger sister and marriage without her parents’ consent, the film was “a logical, human and appealing little story, though dragged out tiresomely in some scenes.” She agreed with the letter writers that Gish “shows herself possessed of a quaint but keen sense of fun, and it is very pleasing to view the young lady whom we have been accustomed to see weeping, playing a prankish part.” The review ran on Wednesday and she mentioned the letters on Friday, so the various persons were annoyed enough to write in right away.

Kevin Brownlow wrote that divorce had been the subject of films since Detected (1903) and while it was commercial, The Children Pay was the first film to treat it with concern and its victims with compassion (Behind the Mask of Innocence, p.34). The film has been preserved at the Danish Film Institute.

Kinglsey liked some of the week’s other releases more than The Children Pay. Her favorite film was a “bright, clean-cut and sparkling romantic comedy” The Prince of Graustark because it “discusses no ‘problems,’ nobody chest heaves or emotes and there is no villain. It is simply a delightfully ingenious comedy, with a smashing surprise finish!”

It’s been preserved at the Eastman House, but in case you’re not planning a trip to Rochester soon I’ll spoil the surprise: Prince Robin must save his country from bankruptcy by marrying a neighboring princess. He refuses and sails to the United States where he meets a wealth financier who agrees to give him the money with the hope that he’ll marry his daughter Maud. He meets a woman whom he thinks is Maud, they go back to Graustark, but she’s not the financier’s daughter, she’s the princess! (I bet you didn’t see that coming!) The novel it was based on is fun, too, and it’s available on the Internet Archive.

Thanksgiving was this week, but Kingsley didn’t miss a column and it barely rated a mention. Special holiday matinees were at the Morosco and Burbank Theaters, and backstage at the Majestic, where A Trip Through China was in its third week, the local Chinese community planned a Chinese Thanksgiving dinner with birds’ nest soup and chop suey for Benjamin Brodsky and his associates.

This was also the week of salary news:

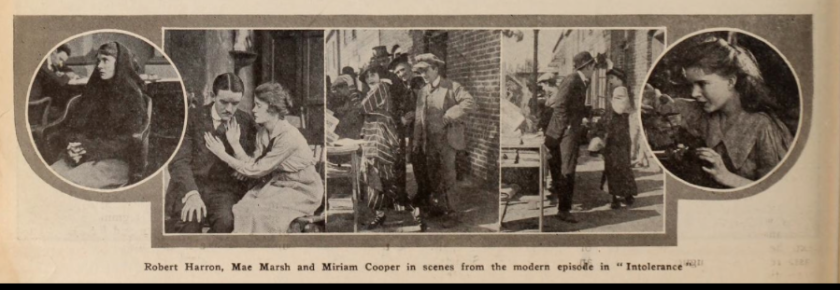

- Mae Marsh was leaving D.W. Griffith and going to work for Samuel Goldfish, who planned to pay her $2000 per week.

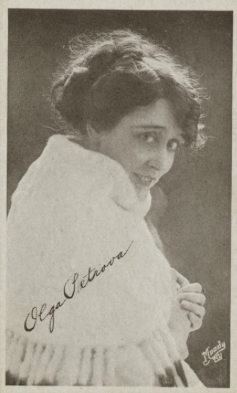

- Olga Petrova left Metro for Lasky, where she was to be paid $4000 per week.

- Douglas Fairbanks was offered $10,000 per week to star in his own company, but his current contract with Triangle prevented him for taking it.

- The Palace Theater in New York announced that dancer Maud Allan was to get $7500 per week, the largest salary ever paid a vaudeville attraction. She was to do a series of dramatic dances. She didn’t get to keep the whole $7500; she was responsible for paying her own orchestra and company.

According to the U.S. News and World Report, in 1915 the average man made $687 per year and the average woman made half that. So it’s no wonder people were astonished by entertainers’ salaries.

Kingsley mentioned an actor’s fashion prediction. “Charles Ray, Ince star, has made the discovery that wrist-watches worn by men are not effeminate – not when you know how they originated and you wear them in the proper spirit—So there!” He pointed out that the custom started among soldiers fighting in the Boer War, who didn’t have a pocket to put them in. He continued “and believe me, the day is coming when more American men than you can count will agree that it is a convenience, not just a fad.”

Of course he was right, but it took soldiers fighting in World War 1 to really change public opinion, according to History.com. Wristwatches had been stereotyped because the first ones were pieces of jewelry worn by women (and obviously, if women do something it must be questionable).

Ray was a popular star until 1923, when the big-budget The Courtship of Miles Standish failed at the box office. He continued to act, but he filed for bankruptcy twice and ended up playing bit roles until his death in 1943.

Finally, Kingsley mentioned that inter titles had hit a new low, when one of the films playing that week included “the announcement of the fact that the heroine’s gentleness is softening the villain: ‘A softening influence has stripped the husks from the eagle’s heart.’” I haven’t been able to find out where it came from; none of the ten films playing seem an obvious candidate for this monstrosity. It’s useful to remember that people in 1916 were not fans of the purplest prose. They had standards, too.