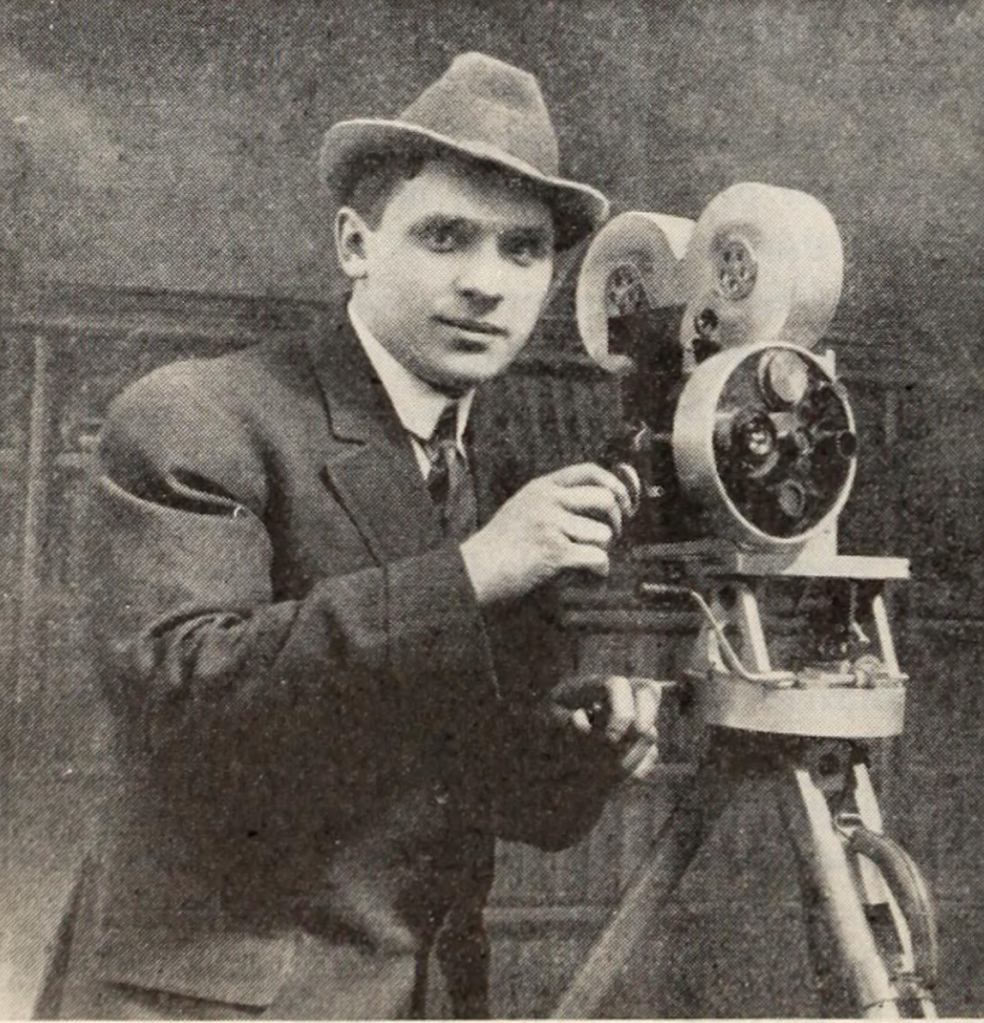

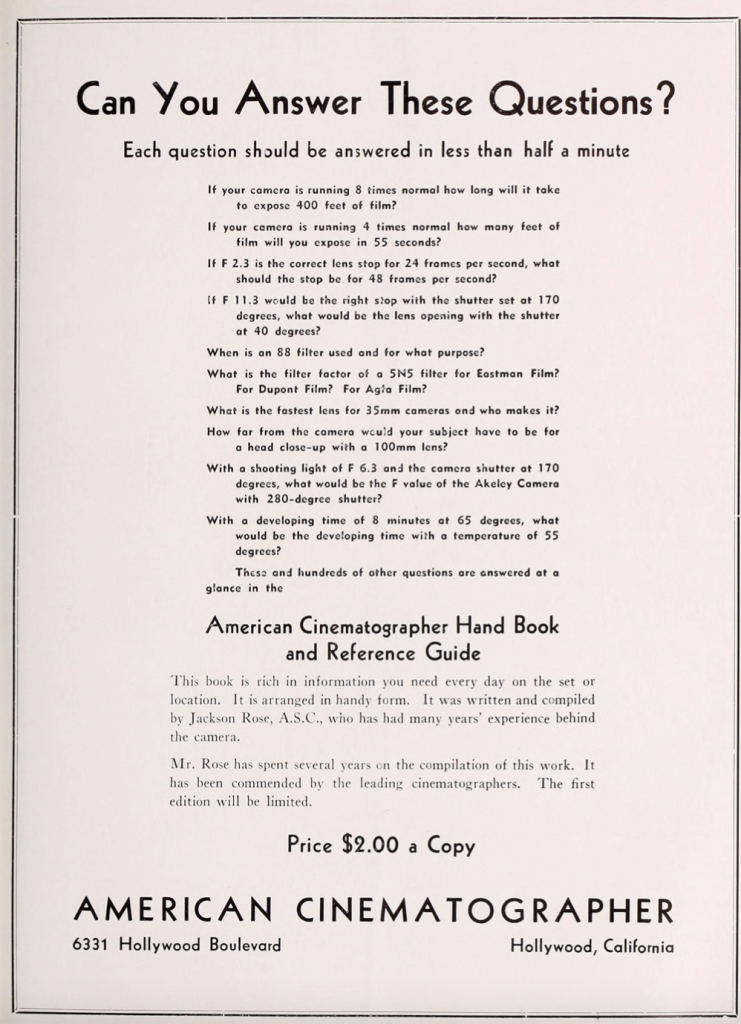

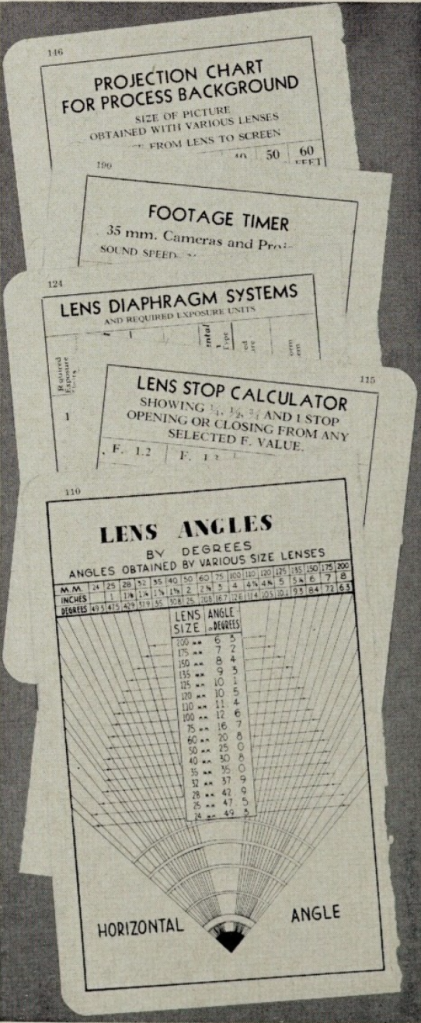

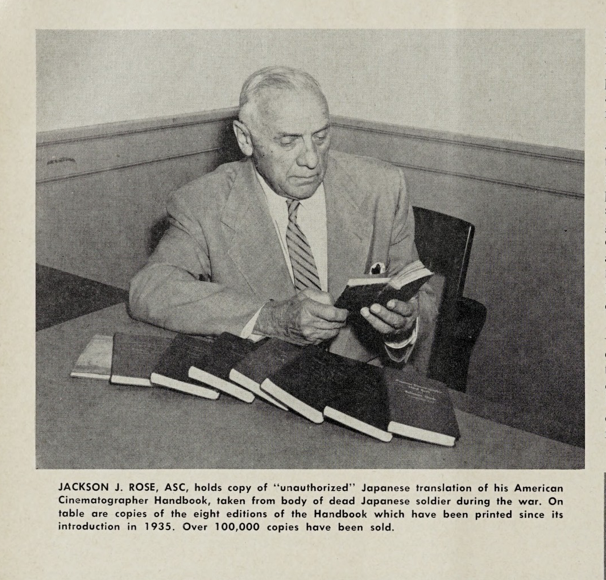

He may not have won any Oscars, and his films aren’t usually taught in film schools, but Jackson Joseph Rose had a solid career as a cinematographer lasting from the early days of the industry until 1952. An ordinary, hard-working director of photography, he was always practical, inventing camera apparatuses, writing technical articles for American Cinematographer and assisting with the founding of the cameraman’s union. But his biggest contribution to cinematography was the book he wrote. From 1935 to 1956, he compiled nine editions of the American Cinematographer Hand Book and Reference Guide. Full of useful information about cameras, lenses, film stocks, and lighting in one handy volume, other directors of photography called it the Jackson Rose Handbook. His book was so essential that the American Society of Cinematographers has continued to update his work; the newest edition came out in March 2022.

Jackson Rose’s parents, Max and Rachel (Silabovsky) Savitsky named him Ike. He was born on October 29, 1886 in Neshvis, Minsk, Russia (now Belarus). He joined his sister, Anna. The Savitskys had another daughter, Esther, before the family immigrated to the United States in 1890. They settled in Chicago, where Max worked as tailor. They had five more children: Abraham (later Joseph), Sarah (later Sylvia), Fred, Samuel, and David.

After Rose left school in around 1898 he became a commercial photographer, mostly shooting stills for advertising. When he married Mildred “Millie” Mendelson on August 18, 1908 he gave his name on their wedding certificate as Jack Savitsky, but by the 1910 census they had chosen the last name Rose.* Millie Rose’s family also had immigrated from Russia in 1893, and in 1910 the couple lived with them in Chicago. Her dad was also a tailor. The Roses had two daughters, Charlotte Ethel on August 5, 1911 and Olive Elaine on September 29, 1918.

In 1910 Rose quit advertising and went to work for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. According to a short biography in a 1917 studio directory, he spent his first year in the laboratory and still departments, then he got promoted to cameraman. Cameramen weren’t mentioned in the credits then, so we don’t know all of films he shot, but in that biography he estimated that he photographed over 225 productions at Essanay. They included One Wonderful Night (1914) with Francis X. Bushman and The Prince of Graustark (1916) with Bryant Washburn, as well as one with their most famous star, Charlie Chaplin. Rose shot his first comedy for the company, His New Job (1915). However, Chaplin hated the Chicago weather and after that he ran back to California.

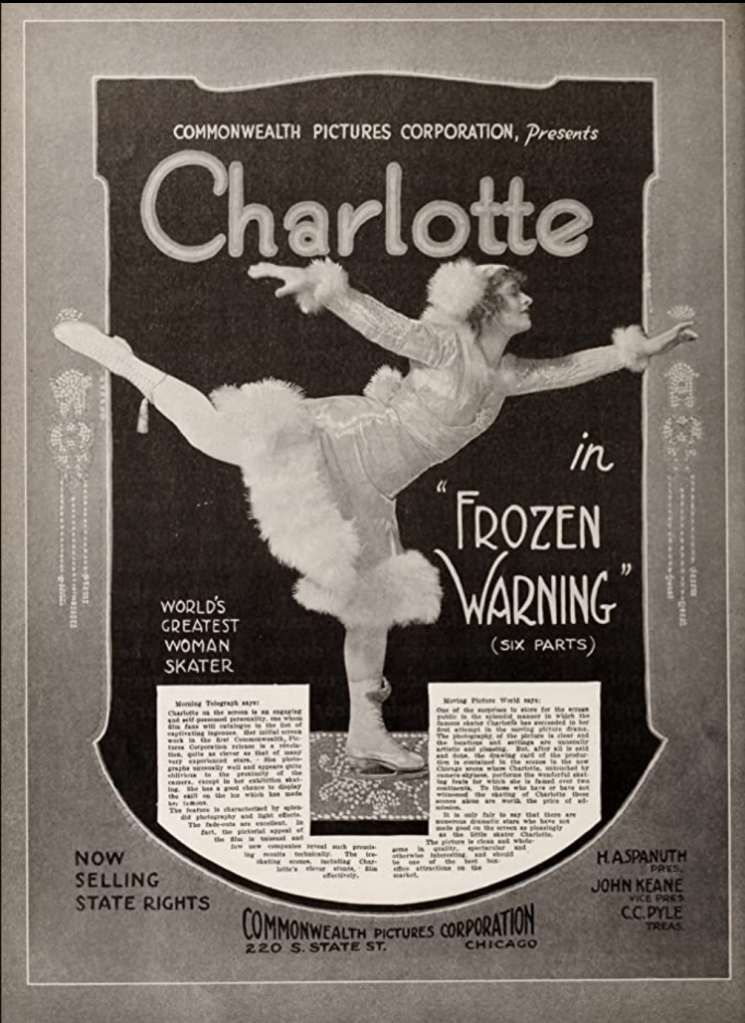

Rose was still working at Essanay when he registered for the World War 1 draft on June 5, 1917, but the company shut down production later that year. By September he was a freelancer, and he got hired by another company in Chicago, the Commonwealth Pictures Company, to make a feature called Frozen Warning starring the “queen of ice skating” Miss Charlotte. Over the next two and half years, he worked for the Calvert-Harrison Feature Film Corporation, Apex Pictures Corporation, Selig, Rothacker and International.

Rose also invented camera equipment — in the early days, cameramen often had to solve problems by building things themselves. In 1917, he wrote about his 800-foot film magazine for Motion Picture News (at the time, most magazines held 400 feet of film). In 1918 he filed for a patent on his Cinema Film Tester, a small box that developed two feet of film in five minutes so camera operators could see how the film would react under location lighting conditions. They didn’t have to wait a day for exposed footage to be taken back to the studio to be developed. His patent was approved on January 4, 1921, but it didn’t get manufactured.

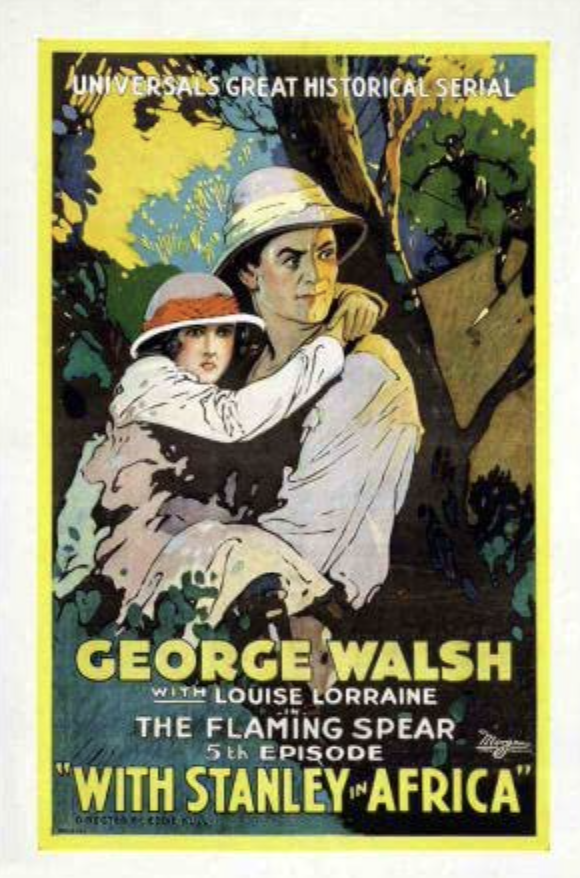

Most film production was moving to Los Angeles, and by January 13, 1920 when the census was taken the Rose family was there, too (a 1944 article mentioned that Mrs. Rose had been suggesting the move since 1916, so she was happy to go). In February 1920 he was hired by Metro Pictures to shoot Burning Daylight, an adventure film based on a Jack London story. He shot six more films for that company, then in 1922, he moved to Universal, where he stayed until 1928. As a cameraman under contract, he shot whatever needed doing, including features like director John M. Stahl’s The Dangerous Age (1922), Smoldering Fires (1925) with Pauline Fredericks, and serials like With Stanley in Africa (1922). While working on the latter, American Cinematographer reported that he “had a bout with a lion the other day and had to climb a ladder to save his bacon. Jack didn’t know until after the excitement that the lion was worse scared than he.”

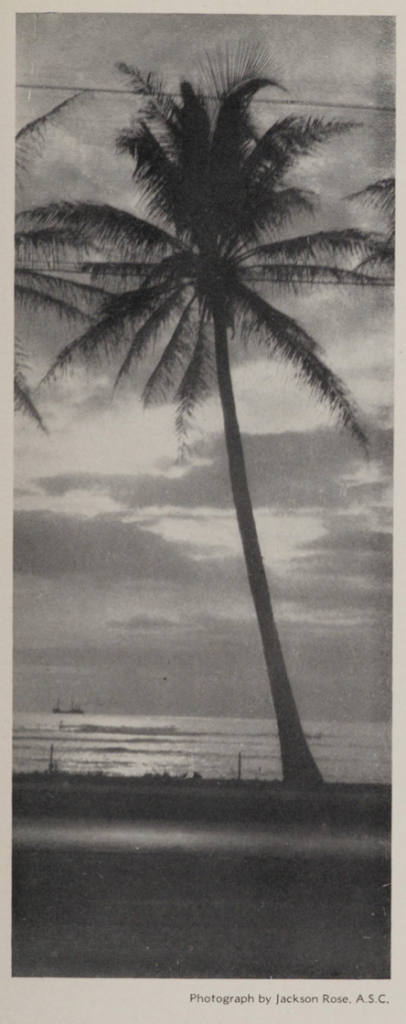

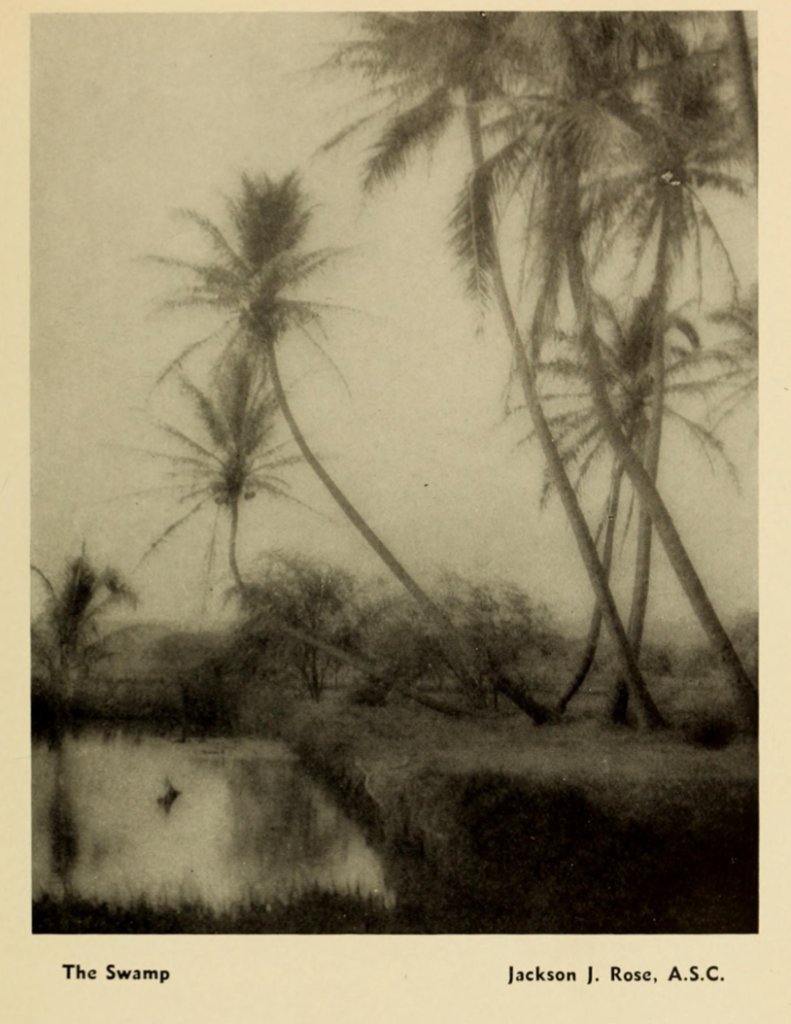

Naturally he soon joined the American Society of Cinematographers, and in 1922 he was elected Treasurer and he served for a year. He regularly contributed to their journal, American Cinematographer. His first article was “How Cameras Act in Honolulu,” in which he reported on his Hawaiian location work on a comedy travelogue; he discovered that the sunlight, despite appearances, was less bright there so he had to increase his exposures.

AC also reported on an even more challenging location shoot for The Foreign Legion (1927). While filming in Guadalupe, California:

Many new ideas were injected in the filming of the scenes in the desert. For the first time, moving shots from caterpillar tractors were used in following an army marching through the desert. For storm effects eight of the largest wind machines obtainable were mounted on tractors to follow the troop, making realistic sand storm effects as they moved along. The resulting pictures were startling, unusual, and very beautiful. Roy Hunter, the head of the Universal camera department, has expressed the opinion that the desert scenes obtained are the most beautiful he has ever seen.

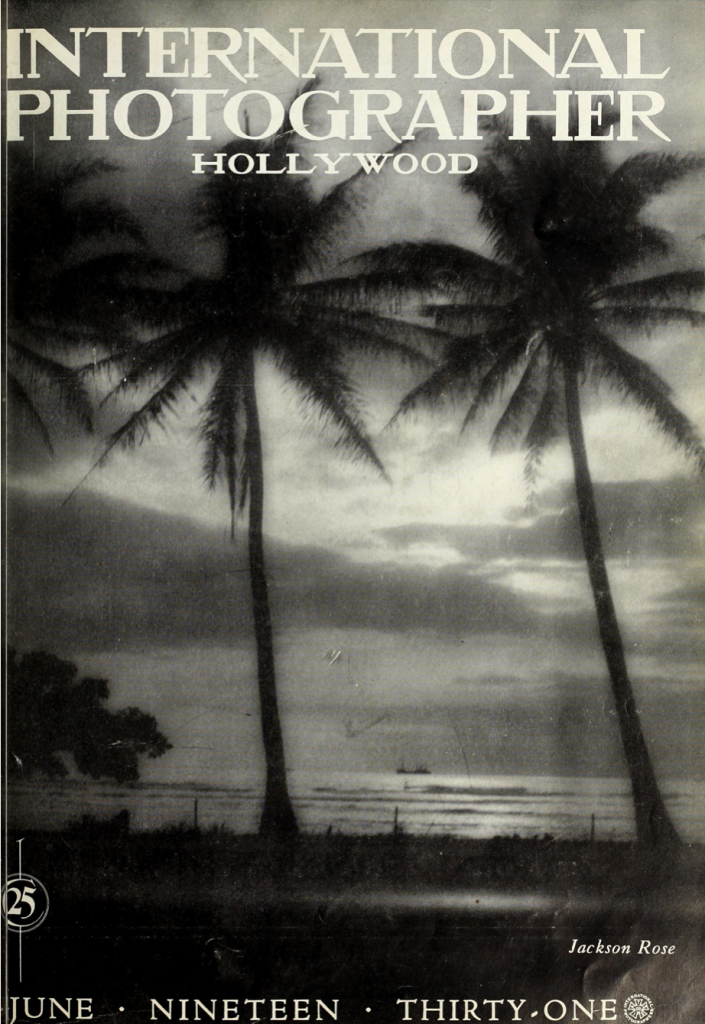

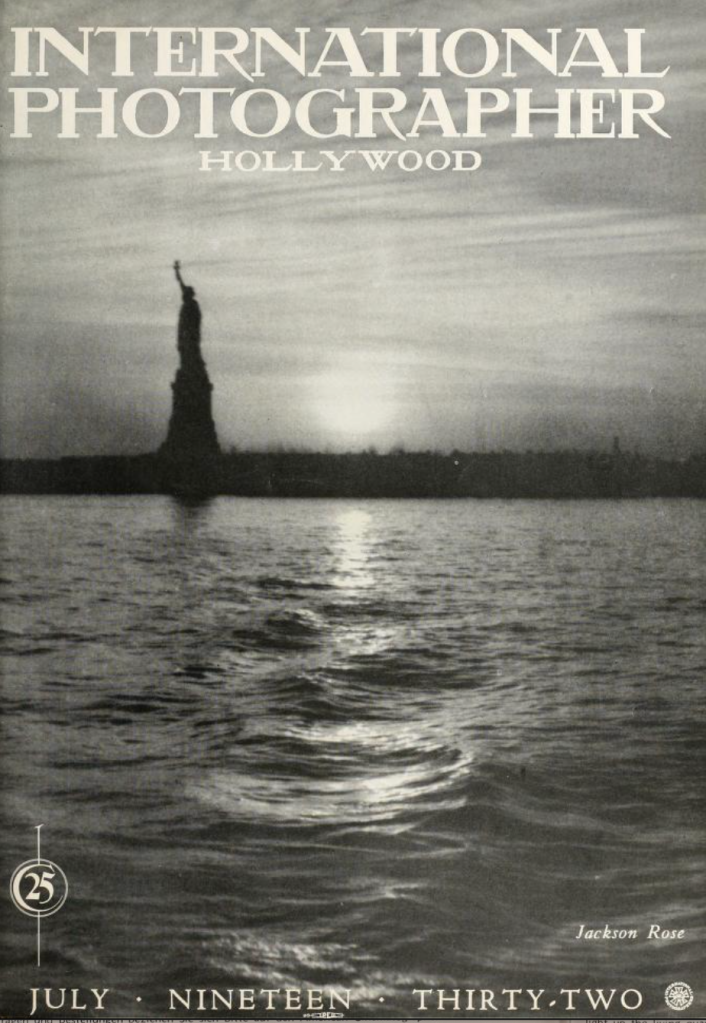

In 1928 he left Universal and became a free-lancer. This gave him more freedom to join the new cameraman’s union when it was chartered on August 1, 1928 as the International Photographers of the Motion Picture Industries, Local 659. He served as their First Vice President from 1929 to 1930 and he chaired the committee that successfully negotiated the first wage scale and bill of working conditions. The union’s magazine, International Photographer, said, “Mr. Rose’s record as a member of Local 659 reflects immense credit upon him. It is not too much to say that he has put in more hours than any other member of the original organizers and, as Chairman of the Negotiations Committee of the organization, his advice and co-operation were of inestimable benefit.”

He resigned from his vice-presidency on May 22, 1930; the reason he gave was that he wanted to “devote a greater part of his time to research along lines of color rendition and other angles of his profession,” but he also might have become busier at his new job. In September 1929, he had gone to work for the Tiffany-Stahl company. It was considered a “Poverty Row” studio, but he was the head of the camera department there. There he got to shoot a variety of films from the early sound adventure film, The Lost Zeppelin (1929) to the drama The Lady Surrenders (1930), directed by John Stahl.

In 1930, he started a new hobby: 16mm amateur filmmaking. He told both International Photographer and American Cinematographer all about his new Filmo 70-D camera (a Bell and Howell camera for the amateur market), projector and screen and he said, “honestly, I get a great kick out of it, for it’s even more interesting to shoot that film than it is to do my regular work in the studio.” He even devised a matte box for his camera in 1931. He contributed articles on lighting for amateur cameramen to AC.

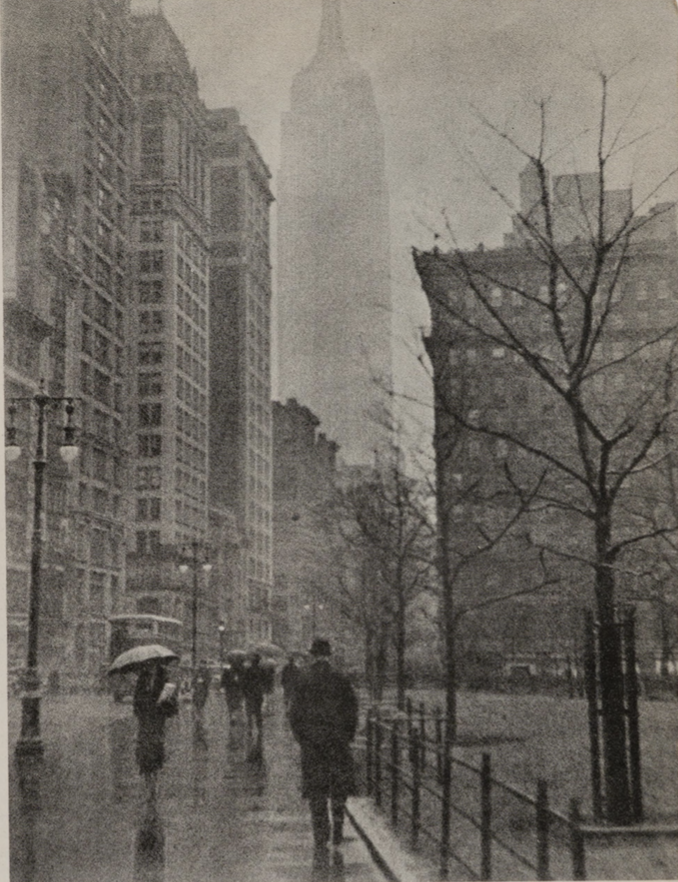

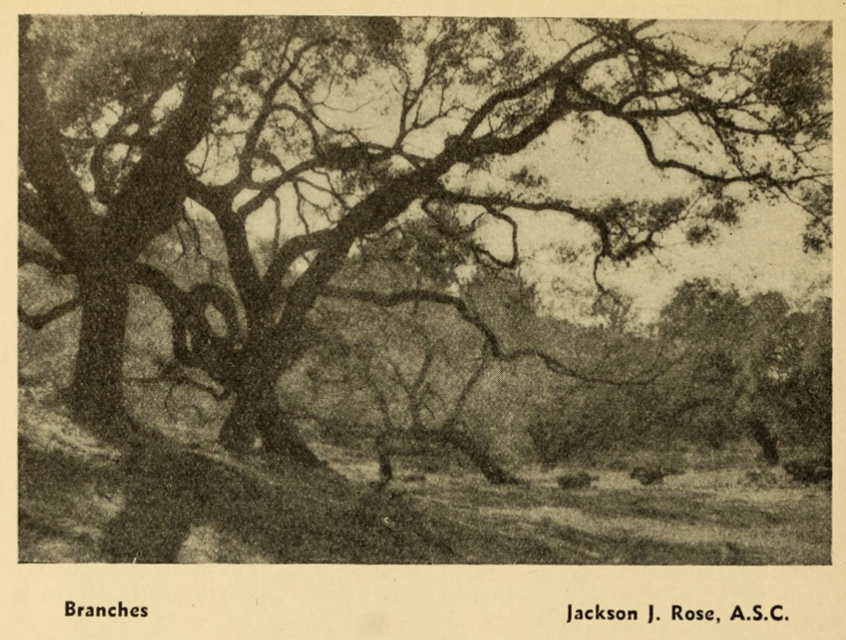

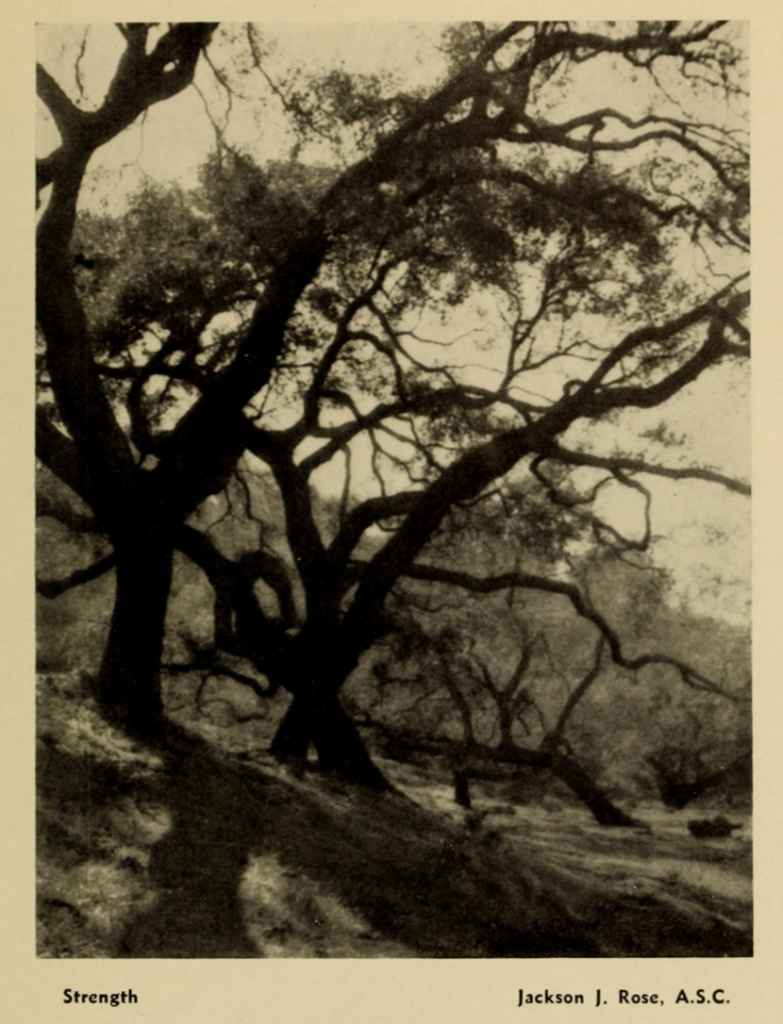

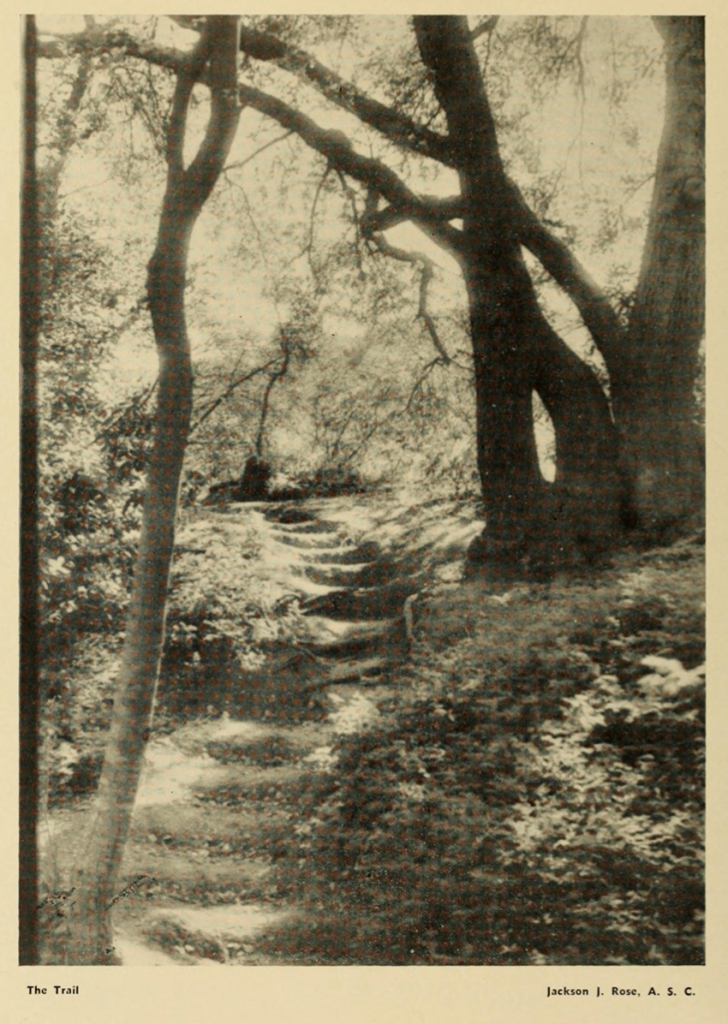

His other hobby was still photography. His work was regularly published in the two cinematographers’ magazines. Of course he invented devices for this, too. For his Leica camera he devised a filter holder, a sun shade, and a new carrying case to hold all his equipment. He also wrote about controlled printing for still cameras in American Cinematographer and entered his work in international exhibitions.

In 1930, the ASC decided to begin publishing the Cinematographic Annual. Like much of the current ASC Manual, this volume was made up of articles written by ASC members on both the art and history of cinematography as well as the technical and practical aspects of filmmaking. For the first one, Rose contributed a piece called “Color Rendition.” It wasn’t about color film; he pointed out that even with black and white pictures “are nothing more nor less than representations of the form and color of a scene in monochrome. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance that cinematographers and art-directors and others interested know exactly how every color and shade will photograph under every condition of lighting and filtering, and upon every make of film.” In a 1944 profile of Rose, W. G. C. Bosco mentioned that it was based on Rose’s tireless independent research:

to complete it he shot tests with every type and make of raw stock, using every type of filter known to the industry, in daylight and under arcs and Mazdas, of every color of the spectrum; and every color was represented by nine shades. It took nearly a year to complete the test, but when it was finished it represented the first really comprehensive and scientific approach to one of the most fundamental problems in monochrome photography ever made.

The ASC published a second volume in 1931 and he contributed “Making Tests with a Small Camera,” in which he made the case that inexpensive experimentation with film stocks and filters could be done with a still camera. The Cinematographic Annual was discontinued after that because they couldn’t sell enough copies during the Great Depression, according to editor Stephen H. Burum in the Ninth edition of the ASC Manual (2004).

In 1932, he was hurt in a car accident. He and director Phil Rosen and two other crew members were riding in a car north of Mojave when the driver, Irving Starr, was driving too fast and went off the road and the car overturned. Rose ended up in the hospital, badly bruised with seven stiches in his scalp and a broken thumb. This ended his time at Tiffany-Stahl, which went bankrupt soon after.

After he recovered, he returned to Universal Studios, where he worked on Radio Patrol (1932) and Don’t Bet on Love (1933) with Ginger Rogers. He also joined the advisory editorial board for American Cinematographer, and he served for one year. In 1934 he started helping answer questions from amateur cameramen about things like film preservatives and neutral density filters for their “Here’s How” column.

Also in 1934 he was hired by MGM as a staff cinematographer. During the next twelve years, he shot a few features like Northwest Rangers (1942), war training films like Fighting Men, documentary shorts, and many Our Gang movies. He also did quite a lot that didn’t turn up in the film credits. In late 1934 he was shooting second unit footage for Mutiny on the Bounty, and “was backing up to get a focus on the next scene. The railing around the camera platform broke, when Jackson pushed against it, and Rose plunged down toward the shark-infested waters below. Rose managed to catch hold of part of the platform and hang there while Syd Wagner and Frank Lloyd took pot shots at the fish in case Rose’s fingers slipped. Finally several grips managed to tie a rope around Jackson’s waist and drag him back up.” This story got picked up by the Los Angeles Times, and American Cinematographer commented “here’s what the studio publicity department considers humor.”

It wasn’t always a full-time job at MGM, the studio called him in when they needed him. For example, in 1940 his daughter Elaine reported to the census-taker that in 1939 he’d worked ten weeks of the year, 54 hours for $3,000 per week. So he had time to work on his most important contribution to his profession, the American Cinematographer Hand Book and Reference Guide.

American Cinematographer writer John Forbes later told how it all started:

“Rose had slips of paper with penciled data in every pocket,” recalls one old-time associate. In time the notes became so numerous they were hard to locate when they were needed for reference again. So Rose bought a small, pocket-size notebook from a dime store and laboriously transferred to it all the data he had gathered up until that time. Additional blank pages were provided, and these received additional data notes during ensuing months.

This diligent data-gatherer was notably free in passing his information on to brother cameramen. Almost daily, those who knew of his pocket compendium of cinematographic facts often stopped him for a glance at the book to get the answer to some problem encountered on their own photographic assignments. Invariably they suggested that Rose have the data printed in handbook form and sell copies to other cameramen.

The original book, Rose told Forbes, contained all the basic charts and tables in almost daily use by cameramen at that time in 84 pages. Packed with information about filters, lenses, cameras and camera set-ups, the ASC sold it to professional DPs and advanced amateurs. It was a success. They sold out all 1000 copies they’d printed, so he updated it and brought out a second edition in 1938. It had grown to 202 pages. He was happy about its success, writing in its introduction:

It is very gratifying to the author, who originally compiled most of this data primarily as a source of hand reference for use in his own work, to find that this information in published for use in his own work, to find that this information in published form has proven so helpful to others that a second edition is necessary.

Over the following two decades, he kept adding to it, and new editions came out in 1939, 1942, 1946, 1947, 1950, 1953, and 1956. By 1955, over 100,000 copies of the Hand Book had been sold. William Stull reviewed the fourth edition in American Cinematographer in 1942, and he said:

During the past ten years the “Jackson Rose Handbook” has become without question the world’s standard practical reference work on cinematography. Today’s Fourth Edition worthily carries on the tradition established by the three successive printings which went before. It includes all of the highly practical photo technical information in the previous editions…Our own experience with previous editions of Mr. Rose’s volume is that it is essential for anyone active in cine or still photography. The new edition bids fair to be even more valuable.

When the census taker visited in 1940, the Rose family was still all together on North Berando Street. Their older daughter, Charlotte, had returned home after a divorce from Bernard Pollock (they were married in 1935) and was working as a stenographer at a movie studio. She later married Joseph Menzon, who was a buyer at a department store. Her sister Elaine was working as a saleswoman in a department store, and she married Norman Litter, a manager at a finance company, in January 1941.

Jackson Rose worked for MGM until 1945, when the studio laid off a lot of their staff. (Eleanor Keaton, who was a dancer there and let go at the same time, called it a “purge.”) He went back to freelancing, mostly on low-budget features like Philo Vance’s Gamble (1947) for the Producers Releasing Corporation and Music Man(1948) at Monogram. In 1950 he shot some shorts for the Protestant Film Commission. He finished off his career with some television episodes of The Buster Keaton Show, and he retired in 1952.

On June 28, 1954 Mildred Rose died of heart failure. She’d been diagnosed with hypertension four years earlier. She was buried at Hillside Memorial Park.

After her death, Jackson Rose kept busy. In addition to working on his Hand Book, he helped the ASC. When the George Eastman House decided to have a film festival and ceremony to honor twenty of the most notable actors, directors, and cameramen from 1915-1925, Rose represented them on the committee chaired by Jesse Lasky. American Cinematographer said, “Rose, veteran Hollywood cinematographer, is ideally suited to the task in view of his early-day Hollywood experiences and his vast library of memorabilia on the industry and its personnel.” He also answered questions in a monthly column for the magazine called “Your Questions.” His subjects included how to keep your film supply safe in humid conditions and what’s the difference between “depth of focus” and “depth of field.”

In September 1955 he was among the 43 ASC members to receive a gold membership card for 25 years or more of membership.

Jackson Rose died on September 23, 1956, eleven days after an operation for bladder cancer. He’d been diagnosed with it five years earlier. He was also buried at Hillside Memorial Park.

The ASC decided to keep his manual going. In 1959 they announced that they would be continuing to update the book. Re-named the American Cinematographer Manual, it combined updated versions of all his charts and tables with articles written about cinematography by ASC members, like the ones in the Cinematographic Annual. It was such a big job that they asked three people to do what Rose had been doing alone. Cinematographer and contributor to American Cinematographer Joseph V. Mascelli was chosen to edit it and former ASC presidents Walter Stenge and Arthur Miller acted as technical advisors and associate editors. It grew to 482 pages long. Since then, the ASC has regularly updated the Manual, and the eleventh edition came out in 2022.

In 2002, the ASC won a technical Oscar for their continuing publication of the Manual; the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences called it “the premier reference book for motion picture cinematographers.” What began as Jackson Rose’s collection of notes in his pocket have become essential to cinematographers’ work. In 1944, W. G. C. Bosco said, “a truly remarkable book, it is a monument to the painstaking genius of a man who has been an ace of the camera from the beginning, Jackson Rose.

If you ever have the opportunity to visit the ASC Clubhouse in Hollywood, be sure to have a look in the glass cases that line the west wall of the conference room/library. There the ASC had preserved Rose’s copies of all his editions of the Manual, and some photos.

*Usually because of antisemitism, lots of Jewish immigrants changed their names. In Rose’s family, his brother Fred changed his name to Sabath, his sisters took their husbands’ last names, and the rest of his family changed their last name to Savitt. One other family member, Sam Savitt, was a cameraman, but he stayed in Chicago and became a newsreel photographer for Universal.

Bibliography:

“About Metro Players,” Motion Picture News, February 28, 1920, p. 2156.

“Another from Jackson Rose,” American Cinematographer, October 1930, p.44.

“The Apex Picture Corporation,” Variety, July 25, 1919, p.28.

“A.S.C. On Parade,” American Cinematographer, December 1942, p. 518.

“The Bacon is Brought Home,” International Photographer, June 1929, pp.12-13.

“Bell and Howell Camera No. 1,” American Cinematographer, October 1924, p. 26.

W. G. C. Bosco, “Aces of the Camera: Jackson Rose, A.S.C.,” American Cinematographer, July 1944, pp. 228, 248.

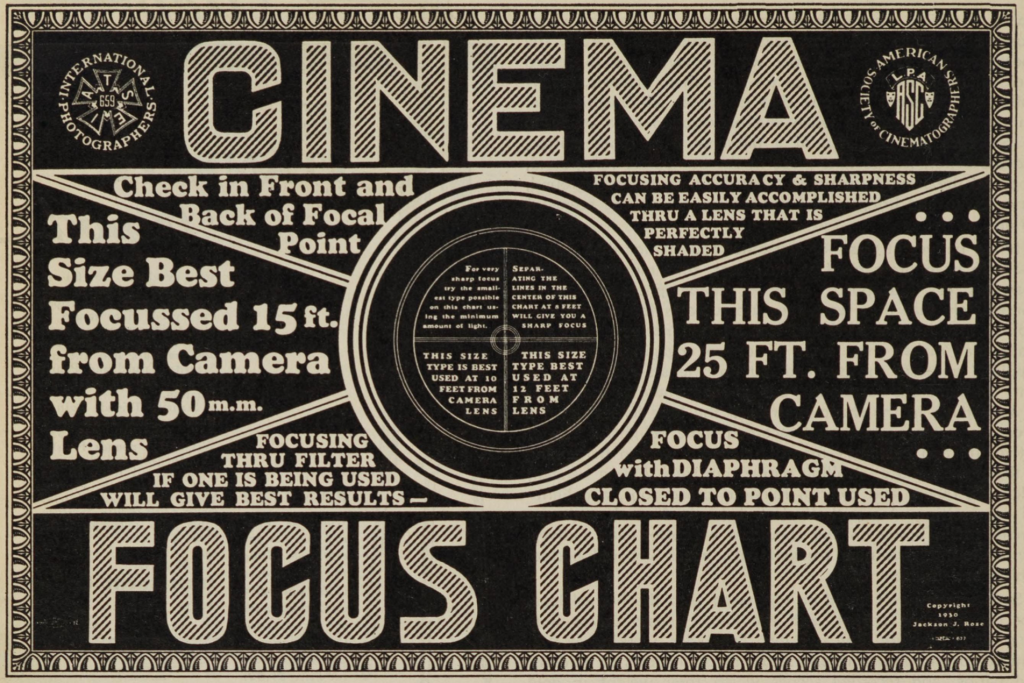

“Cameramen Get Charts,” International Photographer, January 1931, p. 32.

“A Cine Camera of 800 Feet Capacity,” Motion Picture News, December 29, 1917, p. 4610.

John Forbes, “Origin of the American Cinematographer Handbook,” American Cinematographer, July 1955, pp. 400, 428.

“Here’s How,” American Cinematographer, March 1934, p. 4560.

“History Makers of Old Essanay,” International Photographer, May 1930, p.46.

“Hollywood Bulletin Board,” American Cinematographer, October 1955, p. 574.

“In Camerafornia,” American Cinematographer, February 1922, p. 8.

“Industry News,” American Cinematographer, October 1955, p.172.

“Industry News,” American Cinematographer, December 1959, p. 712.

“It is with great regret,” International Photographer, June 1930, p.154.

“Jack Rose Goes Amateur,” International Photographer, April 1930, p.10.

“Jackson J. Rose, A.S.C.,” American Cinematographer, February 15, 1922.

“Jackson J. Rose,” American Cinematographer, October 1956, p.580.

“Jackson Rose, A.S.C., Honored,” American Cinematographer, February 1934, p.429.

“Jackson J. Rose, Cameraman, Essanay,” Studio Directory, April 12, 1917, p.195.

“Jackson Rose, Veteran of Photographers’ Executives, Painfully Hurt in Accident,” International Photographer, September 1932, p. 9.

Read Kendall, ”About and Around in Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times, January 17, 1935.

“KBS in Second Action After Auto Overturn,” Variety, February 28, 1933, p. 26.

“Latest News of Chicago,” Motography, June 29, 1918, p. 1230.

William J. McGrath, “Chicago News and Comment,” Motion Picture News, September 29, 1917, p.2196.

“New Company Formed in Indianapolis,” Motion Picture News, March 8, 1919, p. 1516.

Jackson J. Rose, “How Cameras Act in Honolulu,” American Cinematographer, December 1922, pp. 13-14, 24.

Jackson J. Rose, “Cameramen Need New Viewing Glass,” American Cinematographer, April 1933, pp. 9, 35.

Jackson J. Rose, ”Color Rendition,” Cinematographic Annual, v. 1, 1930, pp.263-271.

Jackson J. Rose, “Controlled Printing for Miniature Camera Pictures,” American Cinematographer, October 1933, pp. 214-5, 257.

Jackson J. Rose, “Home Lighting,” American Cinematographer, January 1932, pp. 24-25, 37.

Jackson Rose, “Lens Facts,” American Cinematographer, April 1949, pp. 334-335.

Jackson J. Rose, “Making Tests with a Small Camera,” Cinematographic Annual, v. 2, 1931, pp. 231-248.

Jackson Rose, “Technicolor Process Today,” International Photographer, February 1947, p. 24.

Jackson J. Rose, “War Economies by “Pre-Photographing” Scripts,” American Cinematographer, March 1943, pp. 119, 121.

Jackson J. Rose, “A Talk on Shooting Locations,” Motion Picture News, August 23, 1919, p. 1677.

Jackson J. Rose, “Your Questions,” American Cinematographer, December 1955, p.696.

Jackson J. Rose, “Your Questions,” American Cinematographer, January 1956, p.14.

Jackson J. Rose, “Your Questions,” American Cinematographer, February 1956, p.72.

Jackson J. Rose, “Your Questions,” American Cinematographer, March 1956, p.140.

“Rose Handbook Ready,” American Cinematographer, December 1941, p. 586.

“Rose to Tiffany-Stahl,” International Photographer, October 1929, p.2.

“’Strangles’ the Camera!” Exhibitors’ Herald, June 4, 1927, pp. 50-51.

William Stull, “Amateur Movie Making,” American Cinematographer, August 1931, p.30.

William Stull, “New Photographic Books,” American Cinematographer, January 1942, p. 18.

William Stull, “Professional Amateurs: Jackson Rose, A.S.C.,” American Cinematographer, April 1930, pp.32-33, 44.

Earl Theisen, “Chaplin,” International Photographer, July 1933, pp. 6-7, 45.

“They’re Together Again,” International Photographer, February 1930, pp 3, 21.

“A Unique Camera Accessory,” Motion Picture News, July 12, 1919, pp. 583-4.

“We have just received word,” American Cinematographer, January 1927, p. 24.

“We Only Heard,” American Cinematographer, April 1935, p. 153.

“With the Pioneers,” International Photographer, April 1929, p. 15.