One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley announced:

Douglas Fairbanks is to stage a spectacular athletic and wild west show on the grounds at his house next Sunday to promote the sale of Liberty Bonds…Admission to the Fairbanks estate at Beverly Hills next Sunday [October 6th] will be absolutely free, but you must prove yourself 100 percent American by purchasing another Liberty Bond from the fifty salesmen who will be on hand to handle the crowds.

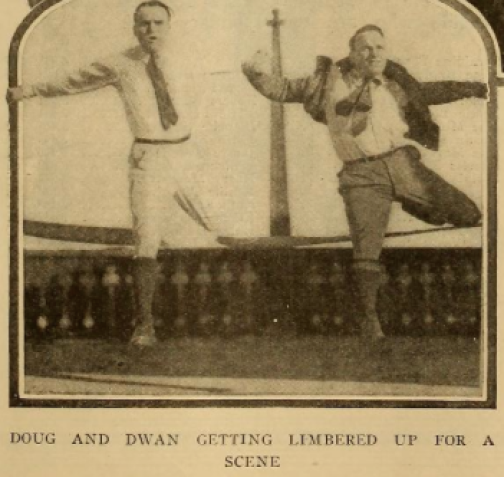

The event included an air show by fliers from the U.S. Army Air Service, boxing, jiu-jitsu, acrobatic and wresting demonstrations followed by a wild west show with 100 “real cowboys” and bucking broncho riding, all to benefit the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive.

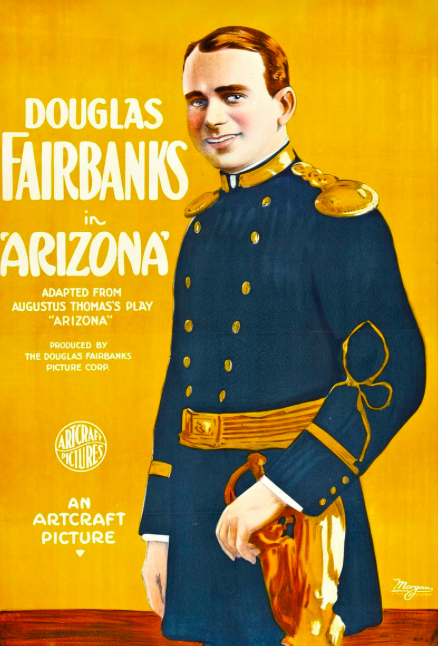

It also offered people the opportunity to see Fairbanks’ estate, where he had shot part of his film that was currently playing at Grauman’s Theater, He Comes Up Smiling. The Los Angeles Herald had a description of the place:

Mr. Fairbanks is the owner of one of the most beautiful homes and attractively laid-out ground in Southern California. It is situated in Beverly Hills, on top of a knoll that overlooks all Los Angeles and affords a fine view of the Pacific. The Fairbanks estate includes 15 acres of grounds, tennis lawn, outdoor swimming pool, war garden, sanitary stables for horses and an immense dog house for Rex, Mr. Fairbanks’ Alaskan malamute.

Unfortunately, we can’t see it now because only two reels of Smiling have survived, and they aren’t the part set at his house.

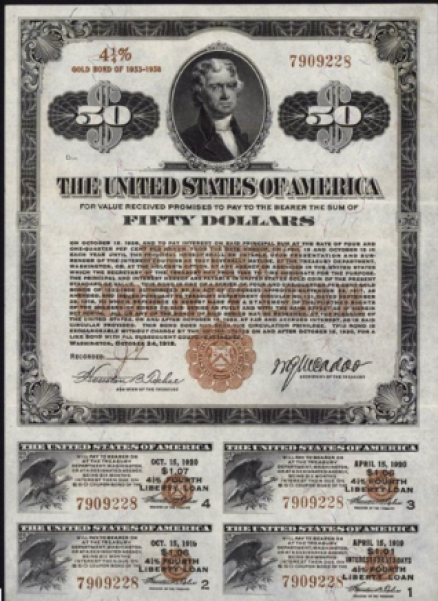

While everyone was invited, this was an event for rich people only, a forerunner to $10,000-a-plate fundraising dinners for political candidates. Admission was pricy: a Liberty Bond cost $50.00. It was a fine investment, but at a time when the average annual household income about $800, many people couldn’t afford it even though you didn’t need to plunk down the whole fifty dollars—just the initial payment of 10 percent. In those more trusting days, if you wanted to pay by check or money order, you made it out to “Douglas Fairbanks.”

Furthermore, it was hard to get to Beverly Hills then: the streetcars didn’t go anywhere near it. Unless you were a very good walker who liked to climb hills, you needed an automobile.

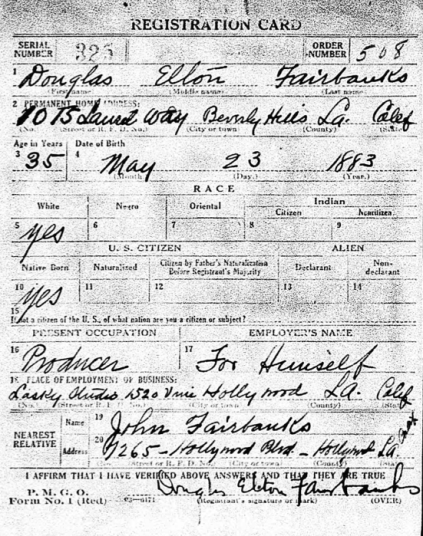

There was another unusual aspect to the event’s publicity: nobody gave the address. An LA Times article breezily said “all roads lead to Doug Fairbanks’ famous house in Beverly Hills this afternoon” as if everybody just knew where he lived. Perhaps they did. The 1918 City Directory was no help; it had an old address on Hollywood Boulevard for him. I had to look up his draft registration to find it, 1015 Laurel Way.

Of course the event was a great big success, just like his rodeo for the Red Cross in January, netting over $106,650 in Liberty Bonds sales plus an additional $2000 for the Boyle Heights Orphanage from the sale of flowers, refreshments and parking fees. Fairbanks stayed in that house until 1920, when he married Mary Pickford and bought Pickfair at 1143 Summit Drive.

This was to be one of the last large public gatherings for nearly two months, because the influenza pandemic had spread to Los Angeles. It started on army bases, then the first civilian case in Los Angeles was reported on October 1st. On Friday, October 11th the Mayor declared an emergency and closed all schools, theaters, churches, dance halls, pool rooms and other public meeting places as of 6 p.m. that day. Even public funerals weren’t allowed. Though officials promised it would only be temporary, the ban lasted until December 2nd. I’ll have more about it in the coming weeks (theater owners were not happy).

This was to be one of the last large public gatherings for nearly two months, because the influenza pandemic had spread to Los Angeles. It started on army bases, then the first civilian case in Los Angeles was reported on October 1st. On Friday, October 11th the Mayor declared an emergency and closed all schools, theaters, churches, dance halls, pool rooms and other public meeting places as of 6 p.m. that day. Even public funerals weren’t allowed. Though officials promised it would only be temporary, the ban lasted until December 2nd. I’ll have more about it in the coming weeks (theater owners were not happy).

Flu disrupted daily life, but it won’t disrupt this blog. Kingsley managed to avoid getting sick — at 45 she was a little bit old for it, because this strain of influenza mostly affected people between 20 and 40. Plus, the ban on public gatherings did help keep the infection rate in Los Angeles lower than in other places. She soldiered on throughout the epidemic, not missing a day of work. She did her best to keep her column filled with cheerful news and gossip, since there was no film or vaudeville to review.

“Film Star Uses Own Home for New Film,” Los Angeles Herald, October 1, 1918.

“Liberty Bond Show Plans Completed,” Los Angeles Herald, October 4, 1918.

N. Pieter M. O’Leary, “The 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic in Los Angeles,” Southern California Quarterly, v.86 no.4 (Winter 2004), pp. 391-403.

“Rodeo Proceeds Reach Large Sum,” Los Angeles Times, October 7, 1918.

Truman B. Handy, “Fairbanks Bond Show,” Los Angeles Times, October 6, 1918.