One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported that the biggest entertainment event in Los Angeles wasn’t film-related, it was on a vaudeville stage, and the most-respected actress of her time was appearing:

It was a hushed house, the silence of which held something akin to reverence, that greeted Sarah Bernhardt, the world’s divine Sarah, at the flag-decked Orpheum yesterday afternoon, when she appeared in Du Theatre au Champ d’Honneur (From the Theater to the Field of Honor) a one-act play written by a French officer…When the curtain went up, the crowd greeted with tremendous cheering the slim little figure in its soldier’s togs, seated beneath a mimic tree in a mimic forest.

The playlet was a story that would only work with the heightened emotions of wartime:

She is a soldier boy, who, on being wounded, has hidden the flag of France to protect it, ere he swooned, and on coming to himself cannot remember where he has hidden it; whose one and only thought is for his country, who is indifferent to the nurses and stretcher bearers who came to find him, and who suddenly remembers that the flag is hidden in the tree, reaches it by an effort, thereby opening his wounds afresh, and passing away as he unfurls the bullet-ridden flag.

The text is available on the Internet Archive.

The performance was interrupted when a woman stood up to cry “Bravo,” fainted, and fell across the balcony railing. Kingsley assumed she was French and was overcome by feelings of patriotism. She wasn’t the only patriot; Kingsley said that “when she cried “God bless America” the audience fairly tore the roof off.”

This was a stop on Bernhardt’s fourth American farewell tour, but this one really was the last. She was 73 years old at the time and still working, despite losing a leg to gangrene in 1915. She died just five years later, in 1923.

It was vaudeville so there were other acts on the bill. It must have been a hard act to follow and they got short-changed for attention in her column, too. “A remarkable bill surrounds the star, including Carl McCullough, with clever travesties of well-know stage stars, Ruth Budd, the marvelous ring and rope worker, Marion Weeks, a dainty young girl with a lovely, bird-like voice; Eddie Carr and company, in a fairly amusing sketch entitled The Office Boy, and the holdovers, Norton and Melnotto, Bensee and Vaird, and Hahn, Weller and O’Donnell.” At least they had a chance to get their acts seen by a large audience.

Kingsley reported on another member of the entertainment industry making a sacrifice for the war effort:

Giving up a $50,000-a-year contract to write film plays for Famous Players-Lasky Company, the brilliant young scenario writer, Frances Marion, who has been able to suit Mary Pickford with roles which fitted like the proverbial glove, is to leave for France next Monday on a patriotic mission.

Miss Marion has received a commission from the government to travel the Allied countries in search of material which will be used as propaganda and which will be published in various magazines and newspapers in this country and possible in England, Australia and Canada. The nature of the material is to relate to the human interest and home side of the war.

She expected to be gone for a year, and first visit France, then Great Britain and later Russia, Japan, China, India and Egypt. However, because the war ended much more quickly than most people expected, her trip didn’t last so long. According to her biographer Cari Beauchamp,* Marion sailed for France on September 18th and reported for duty at the Committee for Public Information in Paris. She was assigned to film the work of Allied women, including nurses, telephone operators, interpreters and entertainers. She saw the devastation brought by the war when she was attached to units traveling to Verdun and later Luxembourg to treat wounded troops during the German retreat. She was flown back to Paris on November 10th, so she was there for the Armistice celebrations the next day. There she caught influenza, but unlike so many pandemic victims, she recovered. She returned to New York in early February 1919, and went on the write all kinds of successful screenplays, from Stella Dallas (1925) to The Champ (1931).

Kingsley’s review of Her Body in Bond this week had some prime complaining:

There are two Mammoth Caves in the United States. One is located in Kentucky, the other under the hat of the man who would change the name of the delightful story from The Eternal Columbine to Her Body in Bond… Of course the change was made ‘for advertising purposes’ (and perhaps the end justifies the means during the present lax season on the photoplay rialto) but whether the clientele that craves bodies in bond and souls for sale will appreciate the daintiness of much of this Universal production is another question.

I was surprised because it had the same plot as Breaking the Waves. A woman “whose love for her partner-husband is so deep that she is ready to barter her body to purchase his recovery from serious illness.” This version was more straightforward – Mae Murray’s Polly got money from an old coot to pay for her husband’s treatment, not some sort of quasi-religious magic. At least Kingsley enjoyed the film, despite the title.

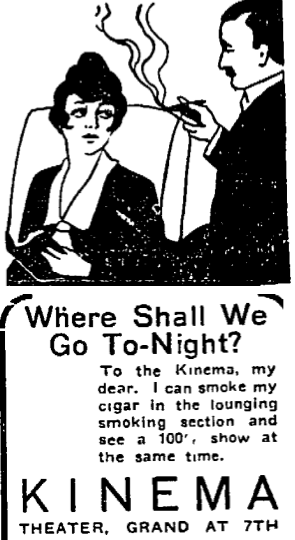

The Kinema Theater added a new selling point this week:

Cigars in an enclosed public space? I’m glad some things have changed in the last 100 years!

*Cari Beauchamp, Without Lying Down: Francis Marion and the Powerful Women of Hollywood. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997, pp. 92-100.

It was the largest and most successful screenwriting school of its time, according to film historian Anne Morey.* By the early 1920’s, she said that with the typical year-long course of instruction, subscribers received several books, twelve lectures, newsletters, a monthly magazine The Photodramatist, and five screenplay critiques. Rates ranged from $76.50 to $90, depending on which plan the student chose.

It was the largest and most successful screenwriting school of its time, according to film historian Anne Morey.* By the early 1920’s, she said that with the typical year-long course of instruction, subscribers received several books, twelve lectures, newsletters, a monthly magazine The Photodramatist, and five screenplay critiques. Rates ranged from $76.50 to $90, depending on which plan the student chose.

I suppose a little exercise isn’t a bad idea for most people, but honestly, nobody would write to him for diet advice: he was fine exactly as he was. (I would believe it if someone asked him for advice on dancing or practical jokes – he knew a lot about both.) This was all a set up for something that I think was supposed to be a joke: since people believed that cold-water baths helped people to reduce, skating on thin ice would lead to a dunking and weight reduction. Paul Conlon, his publicist, was really having an off day. Then again, he did manage to get Kingsley to include this…

I suppose a little exercise isn’t a bad idea for most people, but honestly, nobody would write to him for diet advice: he was fine exactly as he was. (I would believe it if someone asked him for advice on dancing or practical jokes – he knew a lot about both.) This was all a set up for something that I think was supposed to be a joke: since people believed that cold-water baths helped people to reduce, skating on thin ice would lead to a dunking and weight reduction. Paul Conlon, his publicist, was really having an off day. Then again, he did manage to get Kingsley to include this…

With a high-power comedy bear and comedy curls, Theda Bara has wrapped her misery cloak in mothballs…It was a Spanish interior set out at the Fox studio, and naturally you expected to see Theda Bara glide vampirishly forth, dolled up in a slinky frock, or leap into the scene with a nice shiny dagger held aloft, or drag herself sorrowfully in and drop down on the soggy sofa. Nothing of the sort.

With a high-power comedy bear and comedy curls, Theda Bara has wrapped her misery cloak in mothballs…It was a Spanish interior set out at the Fox studio, and naturally you expected to see Theda Bara glide vampirishly forth, dolled up in a slinky frock, or leap into the scene with a nice shiny dagger held aloft, or drag herself sorrowfully in and drop down on the soggy sofa. Nothing of the sort.