One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported on a film industry veteran’s latest job:

C.A. Willat, a pioneer in motion pictures and reputed to be one of the best-informed men in the industry, has been appointed general manager of the West Coast studios of the National Film Corporation of America, according to announcement made by Capt. Harry Rubey, National’s president.

Mr. Willat has been actively connected with the industry since 1904. He is credited with many innovations in production, and was largely responsible for the organization of the New York Motion Picture Corporation, makers of the famous Kay-Bee, Broncho, Domino and Keystone brands of picture play. Under Willat’s management the National will resume its output of features. Mr. Willat is now negotiating with several particularly luminous stars.

Kingsley wasn’t being hyperbolic–he really was part of many production innovations. However, she didn’t mention the one that he’s mostly remembered for: he worked for the Technicolor Film Company in its early days. Willat’s career shows how temporary all jobs in the movies were (and are) outside of the golden days of the studio system. Even for people on the business side it’s an unstable profession.

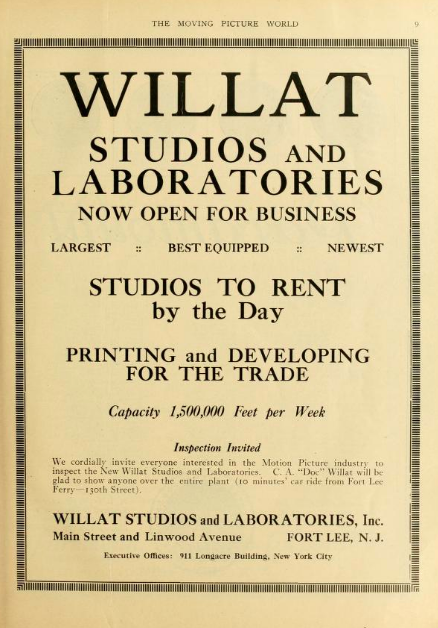

Alfred Carl “Doc” Willatowski* was born November 22, 1878 in Detroit, Michigan. In 1900 he was a salesman living in DeLand, Florida. According to his bio in the 1921 Motion Picture Directory, he became a film exhibitor in 1905, then went to work for Vitagraph in Brooklyn in 1906. Three years later he went to work for Carl Laemmle as the general manager of Imp (he was part of the group that ran away to Cuba to escape the Motion Picture Patents Company enforcement), then in 1911 he was hired to re-organize the New York Picture Corporation. In 1914 he struck out on his own and founded the Willat Studios and Laboratories in Ft. Lee, New Jersey. That only lasted for two years, then he went to work for Techincolor. He was the supervising producer for their first feature, The Gulf Between.

In 1919, he was still working for Technicolor Corporation, and he traveled to London on their behalf to help London Films reorganize their studio. However, with the commercial failure of The Gulf Between, the company had money problems so he left and moved to Los Angeles, where he took the job that Kingsley announced.

Later this year in July, he took on a second job as General Manger of his younger brother’s production company, Irvin V. Willat Productions. (Irvin had been directing films since 1917.) He did both for six months, then he left First National in December.

The Willats built their own studio in Culver City, and Irvin shot his films there until 1924. Its administration building was unique:

Historian Marc Wanamaker has an entertaining post about the building, which was moved and is now a house in Beverly Hills, at the Culver City Historical Society site.

In 1923, Carl Willat went back to work for Technicolor as their Hollywood studio manager. So in 1924 when Paramount was ready to make their first Technicolor film, Wanderer of the Wasteland, they hired Irvin to direct it.

By 1927, C.A. Willat had gotten out of the industry and he had become a real estate broker. He died of pneumonia in 1937. George Eastman said that “Doc” Willat did more for the technical advancement of the motion picture than any other man, according to Kevin Brownlow.

Willet’s brother Irvin lived long enough to chat with film historians, and Kevin Brownlow found him to be quite a character. He wrote about his interview with him for the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. Irvin Willat died in 1976.

Kingsley’s favorite film this week was The Silver Horde. But first, she had to complain about the state of pictures:

All of the plots and combinations of plots having been used up in pictures long ago, so far as the human equation is concerned, it seems as if there remains only the device of placing characters in a new physical setting to give freshness to a screen story, with the setting sharing somewhat in interest.

It was only 1920 and it already seemed like everything had been done before! However have they managed to fill up production schedules over the next 100 years? Nevertheless, she managed to find some entertainment value in a movie this week:

Take Rex Beach’s The Silver Horde, on view at the California, for instance. This has to do with a fight for fishing rights on an Alaskan river between an unscrupulous owner of a great cannery and three gritty pioneers who don’t propose to be put out.

Rex Beach has the knack of writing stories that when produced on the screen are quite actor-proof, director and producer proof. Nevertheless it is pleasant to record that Goldwyn and Frank Lloyd, using a very good cast, have given us a fine and vivid picturization and regards novelty the pictures of the running of the salmon, taken up north, are interesting in themselves.

The Silver Horde has been preserved by MGM, but it doesn’t seem to be available on DVD or streaming.

Kingsley continued to rail against the lack of novelty in a second review, while noting a trend that really irritated her:

Are our picture shows becoming mere dramas of duds? It would rather seem so.

Not but that Irene Castle’s latest picture, The Amateur Wife, at Grauman’s, isn’t a fairly entertaining story. It is. But there’s nothing particularly new in it but the clothes Miss Castle wears. There are more duds than drama. But perhaps that’s what women go to see. I remember a number of ladies at a tea party I attended decrying Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. “What’s the matter? I asked, expecting to hear there’d be some hue-and-cry regarding the morals of the play, instead of which, one sweet young blond thing answered, “Oh, there are no gowns in it!

In the film’s defense, The amateur Wife told the story of a frumpy girl who is made over into a sophisticated woman, so what she wore would have to be a big part of that. The now lost feature probably made that young blond thing very happy, for it did supply plenty of clothes to look at:

*His nickname “Doc” came from his veterinary studies. His Motion Picture Directory bio says he attended Harvard Veterinary College. That school was at the real Harvard — they used to have such a college, but it closed in 1901.

“News of the Week in Headlines,” Film Daily, December 19, 1920.

C.A. Willat, “A Plan for Cutting Film Costs,” Film Mercury, July 29, 1927.