One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported on how theater owners were getting through the influenza epidemic-caused closure:

Landlord owners of theaters are waiving collection of rents of theaters during the closing of their houses due to the prevalence of Spanish influenza, according to reports given in at the meeting of the Theater Owners’ Association, held yesterday [October 28th] at the offices of William H. Clune in the Knickerbocker Building, at which a majority of members was present. That is, 95 per cent of said landlords have already asserted their willingness to forego collections, and the other 5 per cent are said to be wavering on the side of generosity. Authorities have also waived license money, and payment for film has been rebated by film exchanges.

The members of the association are taking the closing situation with cheerful optimism, especially as they feel certain that business will be heavier that ever as soon as the theaters reopen. All report that their houses have been fumigated and thoroughly cleaned, and that in many cases managers have taken the opportunity to have their theaters entirely renovated from top to bottom, including dressing-rooms and lounging rooms, with installation of additional ventilating apparatus.

Kingsley didn’t mention what the TOA was doing behind the scenes to change the order. According to historian N. Pieter M. O’Leary, they were its most vocal opponents and had been working hard to influence the city council to reopen the theaters, sending petitions since the beginning of the shutdown. He wrote:

Within days of the passage of the closing order, the Owners’ Association circulated a petition arguing that the “partial closing law” was failing to check the number of influenza cases in Los Angeles because the public was “permitted and encouraged to congregate in all places other than theaters, churches and schools.” The petition called for the “closing of all places of business except drug stores, groceries and meat markets.” Arguing that their industry was unfairly closed, the Theater Owners believed that if a complete closing order were implemented, a speedier recovery could be made, which would allow all theaters to reopen sooner.

The city council didn’t buy their argument, and the theaters were to remain closed for a little over a month more.

After two weeks of being stuck in the office, Kingsley escaped with a trip to Brunton Studios, which was a lot that rented out stages to independent producers. She wrote an optimistic piece:

Even though at some of the picture studios they’re sadly warbling “if the flu doesn’t get you, the grocery bill must!” while lifeless stages lift skeleton fingers of framework pointing regretfully up at a sky full of sunshine, many of the studios are beginning to get ready for work, including the Goldwyn studios at Culver City, Metro and others.

And as for Brunton Studios, they’re as busy as a gopher on a tin roof! In fact, out there in the sweet sunshine of Hollywood the broad acres of the Brunton Studios look like a cross section of this little old globe, with their colorful bits of pretty nearly every country in the world represented in its picturesque sets.

Among the films in production were a Dustin Farnum western, A Man in the Open, a Bessie Barriscale comedy, Two-Gun Betty, and a Paris-set crime drama written by Sarah Bernhardt, It Happened in Paris. Kingsley’s best anecdote came from the set of Adele, which was one of the last war movies made. Directed by Wallace Worsely, it starred Kitty Gordon and Wedgewood Nowell:

Having been thoroughly choked and kissed by Villian Nowell, director Worsley informs Miss Gordon she’s got to kill him early tomorrow morning.

“What? Kill a man before breakfast?” exclaims Miss Gordon. “Why, I never do!”

So the epidemic didn’t stop independents from working. However, Guy Price, Kingsley’s rival at the Los Angeles Herald mentioned a detail she left off:

Mr. Robert Brunton isn’t taking any chances. For instance, out at his Melrose Avenue studios, he has stationed at the gate a Red Cross nurse with a 100 per cent anti-flu spray, and every person who enters, employee or visitor, gets a generous sprinkling. Some of the actors—the stars are not immune either—are doused five of six times daily, each dousing representing the number of times they exit and enter the studio.

He didn’t say what the spray was, but it had “an odor that would asphyxiate a horse.”

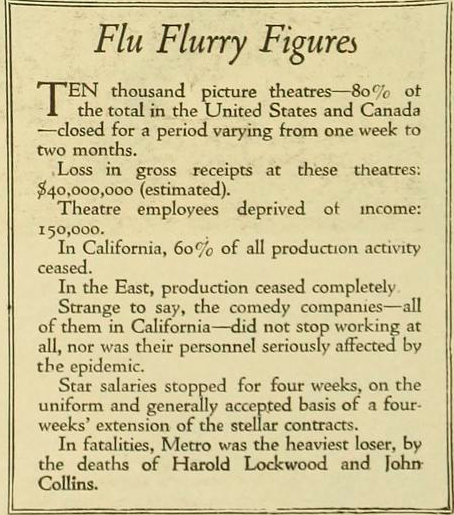

Influenza was causing other problems:

This was one that hadn’t occurred to me!

Pieter M. O’Leary, “The 1918-1919 Influenza Epidemic in Los Angeles,” Southern California Quarterly, v.86 no.4 (Winter 2004), pp. 397-8. (He found the petitions in the Los Angeles City Archives.)

Guy Price, “Footlights and Flickers,” Los Angeles Herald, November 2, 1918.

“I got a seat, too,” she said. “Three men got right up and went out on the platform.”

“I got a seat, too,” she said. “Three men got right up and went out on the platform.”