One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley reported on a production at Universal that was more exciting than it really needed to be. While filming a bar room shoot-out for a two-reel Western called Phantom Gold, director W.B. Pearson asked actor Clarence Hodge to fire a rifle at the film’s star, Fred Church, and instructed him

to place his shots as near as he possibly could to Church’s head without taking the grave chance of “drilling” the leading man. Hodge started to produce excitement from the very outset of the scene. The first shot bored through the edge of the bar above Church’s shoulder. The next whizzed past the place where his forehead had been a moment ago. Ping! Ping! Ping! As fast as the marksman could work the ejector the bullets clipped the edge of the bar within a few inches of Church’s stooping form, and he was showered with flying splinters. The twelve shots in the magazine of the first rifle were fired, and Hodge seized another and kept up the fusillade. The hail of lead was striking so close to the leading man that the director’s nerve gave out, though Church himself was as brave as a Frenchman in battle.

Suddenly the closest shot of all ripped away a piece of wood within two inches of Church’s head, imbedding a splinter the size of a lead pencil in the player’s neck. Right then the director threw up his hands and stopped the action. Twenty-one bullets of 30 caliber were fired, and every one of them landed within three inches of the edge of the bar, which was shattered completely. Church’s hair—which may be assumed to have been in a upright position—was matted with splinters, which also were stuck in his neck and shoulders so that he had the bristling aspect of a scared porcupine. While the handsome film idol declares he had perfect faith in Hodge’s marksmanship, still he admits to a hoping in his inmost soul there will be no retake.

And that’s why unions and workplace safety regulations are so important! From the beginning, actors usually used blanks in guns, not live ammunition. They just didn’t show the effects of bullets hitting things. Now squibs (miniature explosive devices) are used to simulate bullet impacts. Wikipedia (I know, not the best source) says they were first used in Pokolenie (A Generation), a 1955 Polish film.

Phantom Gold is so lost that there isn’t even an IMDB page for it, but it was mentioned in Motion Picture News (July 21, 1917). Clarence Hodge, who learned to shoot in the Army, gave up acting in the early 1920s and went to work for a refrigeration company. Fred Church made it through that workday and had a good long life, dying in 1983 at age 93 of congestive heart failure – not of bad decisions by a director. He mostly acted in Westerns until the mid-1930s, when he retired. Poor W. B. Pearson didn’t fare as well: he died only fifteen months later, in the influenza epidemic.

Kingsley’s favorite film this week was a circus story: ‘all innocent of fights, automobile accidents, fires and seductions as it is, yet The Sawdust Ring, at Clune’s Auditorium, holds you completely charmed.” Bessie Love starred as a girl, deserted by her father, who with a neighbor boy runs away to the big top. Kingsley didn’t catch they boy’s name, but she thought he rivaled Jack Pickford and “he is certainly some little actor!” He was Harold Goodwin, and he went on to work in film and television continuously until 1968, most memorably in Buster Keaton’s College and The Cameraman, as well as in Keaton’s TV shows. The film survives in a shortened version at the Pacific Film Archive and at the BFI.

Here’s how the newspaper used to cover salacious gossip:

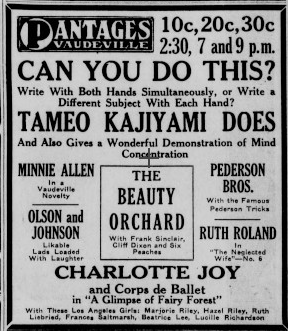

The pages of Frances White’s supposedly private affairs continue to be painfully public. Eastern papers carry the story that detectives on the trail of Miss White’s husband, Frank Fay, discovered him living at a Philadelphia hotel with another woman, and in the meantime, Frank Fay, just to keep things moving, is suing Billy Rock, Miss White’s professional partner, for the alienation of Miss White’s valuable affections.

It was so much more polite! Of course I had to know what happened next. White, a successful vaudeville singer, got her divorce (the marriage lasted all of two months) and Fay’s suit was dismissed – White and Rock were strictly professional partners. Fay went on to have a lucrative career as a stage comedian and master of ceremonies, but his personality didn’t improve: he became a white supremacist. The title of Trav S.D.’s article about him was “The Comedian Who Inspired Hatred.” He was also Barbara Stanwyck’s first husband and their story was rumored to have been the basis for A Star is Born.

Why would someone want to withstand his charm?

Grace Kingsley was wrong about something this week in her review of a Pauline Frederick film, Her Better Self. She seemed to think that it was a problem with the picture when every young woman in the film fell in love with Thomas Meighan: “no feminine being who meets him seems able to withstand his charm, and this though he doesn’t vamp ‘em one bit.” As anyone who has seen him in The Canadian (1926) knows, this is pure realism and solidly logical. To prove my point, here are some more photos.