One hundred years ago this week, soldiers were beginning to come home.

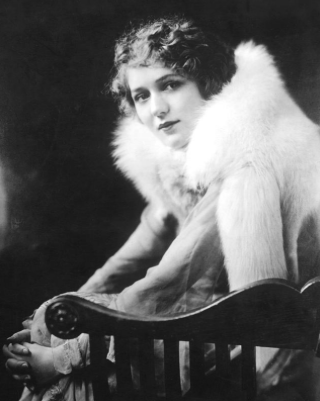

It isn’t every girl who has the luck to welcome even one soldier boy back from France, much less 2000 of ‘em. But that’s to be the delightful privilege of our own Mary Pickford, who will personally wish a Happy New Year to the One Hundred and Forty-third California Field Artillery. Hastening back home from the world war is the gallant 143rd, which, you will recollect, was adopted by Miss Pickford when the boys were at Camp Kearney. Yesterday Mayor Rolph of San Francisco telegraphed Miss Pickford that her godsons would arrive in San Francisco on New Year’s Day, and invited her to be present to welcome them at the ferry and proceed in the parade with them to the Presidio, where special exercises will be held. Mary is to be asked to make a little speech.

However, they had so many ceremonies to attend in New York that their arrival in San Francisco was delayed until January 3rd. Miss Pickford put off her trip, too, and she was there to greet them when they arrived.

The 143rd weren’t only adopted by Pickford, they appeared in her film Johanna Enlists. Russell at Screen Snapshots has a nice article about the film and the troop, including that they were fortunate, and weren’t involved in the fighting in France.

Happily, life was beginning to return to normal but according to economist E. Jay Howenstine, Jr., demobilization wasn’t simple. The government feared mass unemployment when the soldiers returned, so they considered slowing it down. However, every industry wanted their workers back ASAP, and they lobbied their congresspeople to speed things up. Families and the soldiers themselves also pressured their representatives, so by mid-February they were bringing people back as fast as they could, limited only by the number of ships they had. By early June they were discharging 102,000 people per week and by August 1st there were only 156,000 men left in Europe. Almost 4 million individuals had been an American service member, but by the anniversary of the war’s end, demobilization was complete.

Kingsley interviewed D.W. Griffith this week, and he said that he’d made a seven-reel feature out of the Babylon episodes of Intolerance by expanding the love story of the Prince and Princess, as well as the Mountain Girl’s (Constance Talmadge) romance with the Rhapsode (Elmer Clifton). Kingsley wrote:

Here’s a pleasant surprise for you! In the new story, the little Mountain Girl and her lover live! “You see, that’s how the original story was made. Then we changed it. But we kept that film. I’ve allowed the lovers to live this time,” he smiles, “and they go away into the desert together. No, I really don’t know what becomes of them after that, but it must be a very fascinating thing to do, mustn’t it—going away into the desert with one’s lover.

The film was called The Fall of Babylon and contemporary critics like Julian Johnson liked it, saying that on a second viewing he realized his original enthusiasm for Intolerance was merited. A modern critic writing for MOMA mentions that Griffith made it to help recoup his losses. Babylon has been eclipsed by the other film derived from Intolerance, The Mother and the Law. The MOMA writer said the modern story “stands on its own as one of the director’s major achievements.”

Kingsley’s favorite film this week was yet another reworking of The Taming of the Shrew called She Hired a Husband, starring Priscilla Dean. She wrote:

There are several new angles to the old tale. For one thing, you’re sure to be surprised—but I won’t spoil your anticipation of the ending. Of course, you shouldn’t be surprised, because the long arm of coincidence, which is forever reaching out in the film drama—but there, I’ll be telling in a minute!

Instead of being properly tamed at the right time, out there in the cabin in the woods, this chaste and chased Diana, who refuses to be married to anybody her guardians want her to espouse, and picks up with a tramp instead, is kidnapped by real ruffians. And not another word shall I tell you. Go and see the picture for yourself. You’re sure to be vastly entertained.

It’s a lost film, so we can’t be vastly entertained any more but I won’t leave you in suspense: the tramp rescues her from the kidnappers, and it turns out he was the nice young man that her family wanted her to marry all along. Aren’t you glad you were sitting down for that?

This week, Samuel Goldfish legally changed his name to Goldwyn.

Mr. Goldfish decided to name himself after his big organization. Not only, says Mr. Goldfish, has he missed some attractive invitations to dinner, through people thinking his name was Goldwyn, and thus addressing him in nice little notes, but sometimes there has been delay in business negotiations through the same misunderstanding. During the past two years of the company’s existence, in fact, fully half of the mail intended for him, says the new Mr. Goldwyn, has been marked “Samuel Goldwyn.”

It seems the Selwyns, who contributed the last part of the company name, didn’t have the same trouble. It’s funny that he felt he needed to make an excuse for changing his name.

I hope your New Year is as happy as the 143rd’s was!

I hope your New Year is as happy as the 143rd’s was!

Jay Howenstine, Jr. “Demobilization After the First World War,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, v. 58 no, 1 (Nov. 1943), pp. 91-105. This article is particularly interesting because he wrote it to offer suggestions on how to demobilize after the Second World War, putting history to good use.

Julian Johnson, “The Shadow Stage,” Photoplay, October 1919, p. 76,78.