One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley gave some remarkably early publicity to a big-budget film that wouldn’t even have its Los Angeles premier until March 9, 1921. She began by pointing out one of the problems the advertising needed to overcome:

There are a lot of film fans who aren’t going to become excited over the title, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Maybe the soda jerker and the truck driver and the waiter never heard of the Ibanez novel and don’t know a thing about it. As Fatty Arbuckle remarked the other day, “Those guys will probably think the four horsemen mean Tom Mix, Bill Russell, Bill Hart and Harry Carey.”

But when those worthies see the picture—ah, then, I’ll vouch for it, they’ll one and all pronounce it a knockout.

It hadn’t occurred to me before, but the title really isn’t a strong selling point. Now silent film fans know that Four Horsemen was one of the biggest hits of the 1920’s, but at the time, the studio had reasons to worry about it. The biggest problem was that people were sick of war films. Even Mack Sennett joked about it in his ads:

Kingsley explained that this film was different from the rest:

The regenerating influence of the war really is the motif of the story. So that when you hear the name The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, you need not throw up your hands and cry “Another war picture!” Metro isn’t going to do it that way. While the story is a story of the war, it’s not, for the most part, about the war, if you recognize the distinction. Rather, it’s a record of the reaction of the war on a group of intensely human and interesting characters.

Kingsley got to interview the film’s director, Rex Ingram, and the scriptwriter, June Mathis. Even though they promised it wasn’t an ordinary war picture, they said they battle scenes would be historically accurate; former army officers had been hired to make sure it was all correct.

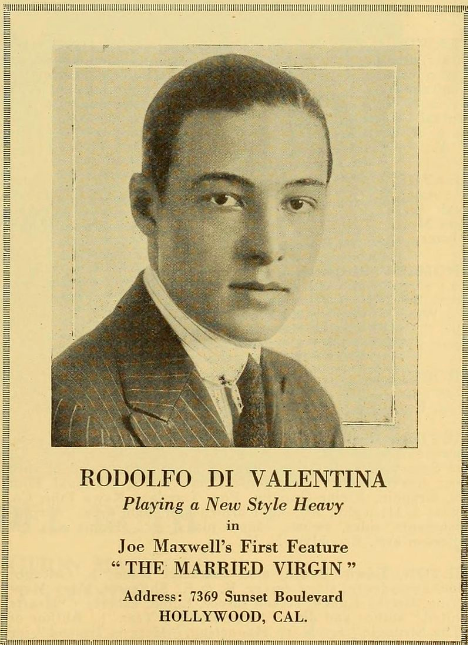

“There are experts for everything. And all the experts disagree, declares Ingram, tearing his hair. “If war is hell,” said Ingram, “making war pictures is purgatory. I had Rudolph Valentino in Seventy-fifth Infantry uniform and one of the war experts came to me and told me there was no such regiment as the Seventy-fifth French Infantry. We were about to yank Rudy out of his clothes, when along came another expert and told me that there was such a regiment, just as I had thought. We investigated and found he was right, so Rudy didn’t have to change his clothes after all.”

“Of course, a lot of them were in the war,” said Miss Mathis, “ but most of ‘em were too excited to know what it was all about.”

All of that trouble paid off. As usual, Kingsley didn’t get to go to the premier of an important film, but her boss Edwin Schallert did and the realism is what impressed him the most:

In the realism of its characters and the quality of its atmosphere, the Four Horsemen reflects superlative credit on its makers. An interest that would otherwise be remote is pertinent simply through an accuracy of delineation, that causes you to fall under the spell of actuality. The feature bears the stamp of authority which grows out of the fact that it represents expert work, not the experting of one or a few, but of many.

Kingsley was right that the non-novel reading public would buy lots of tickets for the film. It played to capacity houses from March 9 to May 3 at the 900-seat Mission Theater.

In other publicity news, Kingsley reported that former film and current theatrical star Olga Petrova was making sure that she would have press coverage, even when she was on vacation.

Mme. Olga Petrova doesn’t believe in taking so important a step as going to Europe, where just anything may happen, without having a personal representative and a special writer along. She has chosen a famous one, viz. Louella Parsons, formerly film editor of the New York Telegraph. The two left for Europe last week and will remain abroad several months.

Publicity during a trip to Europe had recently worked out awfully well for Pickford and Fairbanks, but Petrova didn’t get the publicity boost she hoped for. Parson’s biographer Samantha Barbas explained, “A cold, formal and often temperamental woman originally from Britain, Petrova began to irritate Louella, and Louella, the quintessential tacky tourist (she constantly snapped photos and was “everything you have ever read about the typical American abroad,” she admitted), soon annoyed her friend. After a fight, the two parted in London.”

Oh well. Petrova’s career managed quite well without a writer along.

Finally, Kingsley discovered a new use for homemade beer:

The greatest inventions after all are usually the simplest, says George McDaniel, picture star. Take home brew, for instance. It recently made a record for itself as a burglar alarm in the home of Mr. McDaniel. Burglars broke into the McDaniel residence in Glendale last Saturday night, and just as they were loading the family silver into a gunny sack, one bottle of home brew exploded like a pistol shot, causing the burglars to leave hurriedly just as McDaniel appeared on the scene.

Strictly speaking, home brewing was illegal during Prohibition, but Kingsley wasn’t the least bit worried about letting the police or the public know an actor had an illicit substance in his house. From the beginning, nobody respected the Volstead act.

Samantha Barbas, First Lady of Hollywood, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

“Notable Success of The Four Horsemen” Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1921.

Edwin Schallert, “Reviews,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1921.