One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley offered a preview of yet another movie palace to open in downtown Los Angeles, Grauman’s Million Dollar Theater:

The moment you step out of the work-a-day world into the outer foyer the charm of the place is upon you. There, lining either side wall, are two immense mural paintings in pastel shades but of heroic design. Then there’s the handsome lobby, from which lead wide stairways to the mezzanine, which is heavily carpeted and which yields visions of tapestries, statuary and mural panting in bold and brilliant design.

Ah, but it is the long vista of Gothic arched galleries which will charm you into some age-old dream. And a surely as you have imagination, this dim, beautiful vista, whose somewhat severe beauty is relieved only by the classic sweep of its arches, the soft carpets and half a dozen niched bronze statues, will carry you back to some feudal castle of long ago, and you’ll forget that butter has gone up and that street assessments are due.

The carvings, murals and statuary together re-told John Ruskin’s “The King of the Golden River,” which she thought was quaint and delightful, and it gave “a romantic quality to the whole decorative scheme.” The story, written in the style of a fairy tale, told of two greedy brothers who abuse their kind younger brother and grow rich through their evil enterprises. The younger brother inherits the money when the elder ones get what they deserve. Ruskin wrote his only work of fiction for his future wife Effie Grey when she was 12 years old (their story has been told many times, most recently in Effie Grey (2014)).

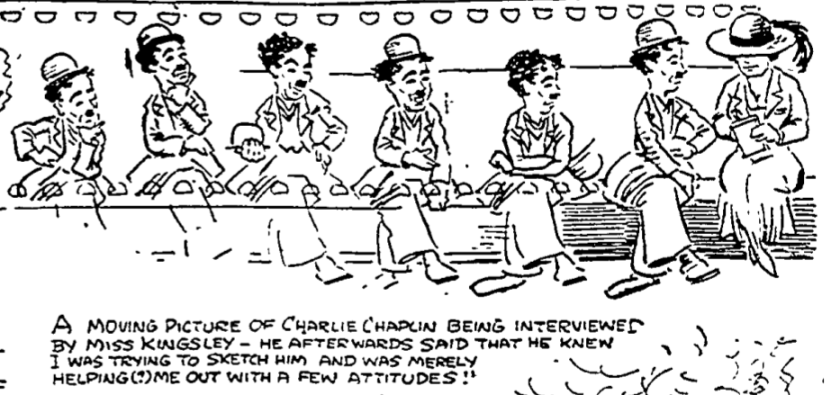

The opening film was The Silent Man with William S. Hart, who made a personal appearance. There was also had a special musical program for that night, with a thirty-piece orchestra, a guest organist, Jessie Crawford, and a coloratura soprano from La Scala named Lina Reggian, who was beginning an engagement of several weeks. All the stars in Hollywood turned out for the event, including Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Roscoe Arbuckle and the Gish sisters. The line to get in was four abreast, jammed like sardines, and it stretched more than two blocks down Broadway.*

It’s remarkable how much movie viewing had changed in a very short time. Kingsley included a picture of what theaters were recently like:

Remember the picture houses we used to attend only four short years ago? Dark, smelly little holes in the wall, most of them, at the door of which a mechanical orchestrion ground out a dreary round of tunes which didn’t pretend to have any relation whatever to the picture or its theme…and where seats on the sawdust-covered aisle were much sought by the tobacco-chewing fraternity.

Nowadays, cell phones in theaters are bad, but at lest we don’t have men spitting in the aisles! She contrasted this with a trip to the cinema in 1918:

It’s getting so nowadays when a friend asks you to go and see a picture, you take for granted the invitation includes a lot of other things. There’s a concert by a symphony orchestra, a loitering trip through long vistas of gallery fitted up with pictures and statuary, a smoke (if you wish) and a bit of a flirtation in the luxurious lounging parlor, even a nice dish of lady-like tea if you desire.

The Million Dollar Theater was the third 2500-3000 seat venue to open in the previous year at a time when the population of Los Angeles was only 576,673, according to the L.A. Almanac. While people went out to the movies more often then now, that was a lot of seats to fill. It’s no wonder that the owners of the other recently opened big theater, the Kinema, couldn’t make a profit and sold it in 1919.

Sid Grauman had much better luck. The Million Dollar (reports were that it cost that much) was his first theater in Los Angeles. He had gotten his earliest experience as a theater builder in Dawson City during the Klondike Gold Rush (as you probably saw in Frozen Time), and he and his father went on to operate several more in the San Francisco area. He was to build the Egyptian Theater (1921) and the Chinese Theater (1927) in Hollywood.

Grauman was busy with his Hollywood theaters so he sold the Million Dollar to Paramount in 1924. It had a variety of owners until 1950, when Frank Fouce bought it and made it a Spanish-language film and stage venue. Grace Kingsley was still writing for the Times, and she attended that grand opening too:

Like a blooming matron with lifted face and full of vitamins, the handsome, durable Million Dollar renews her youth. Beautiful decorations and furnishings make the place glamorous. It recalls that first opening on February 18, 1918**, when Sid Grauman brought myriads of stars to the theater…On that occasion, too, just like last night, crowds blocks long waited to get into the theater. The late Antony Anderson, critic, fairly lifted this reviewer out of a crowd that threatened to crush her.***

She also really enjoyed the Cantinflas film that opened it, Puerta, Joven. (aka El Portero) Even without English subtitles, “so vivid is his pantomime that it is likely the story can be traced even by non-Spanish speaking spectators.” The film was Cyrano crossed with City Lights.

The theater became a church in 1993 and was closed in 1998, but it was restored and reopened in 2008. Now it’s available for film shoots, special events, and even occasional film screenings. What’s really amazing is that much of what Kingsley described is still there: the murals are just waiting behind a drop ceiling and covered walls, according to the L.A. Conservancy. Somebody with big bags of money could restore them.

*”Opening’s Brilliant of Million-Dollar Theater,” Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1918.

**It was actually February 1, 1918. Ooops!

***Grace Kingsley, “Gala Premiere Reopens Million Dollar Theater,” Los Angeles Times, August 31, 1950.

Frank Lloyd had a long and impressive career that included five Oscar nominations for best director and two wins, for The Divine Lady (1929) and Cavalcade (1933). Now his most remembered films are Oliver Twist (1922) The Sea Hawk (1924) Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and Under Two Flags (1936).

Frank Lloyd had a long and impressive career that included five Oscar nominations for best director and two wins, for The Divine Lady (1929) and Cavalcade (1933). Now his most remembered films are Oliver Twist (1922) The Sea Hawk (1924) Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) and Under Two Flags (1936).