One hundred years ago this week, Grace Kingsley had it on very good authority that the new dance craze wasn’t immoral:

You may shimmie, if you wish! So says Marion Morgan, producer of the Morgan dancing act, which is creating a sensation at the Orpheum this week. And you may take Miss Morgan’s word for it, ‘cause she used to be a school ma’am in days gone by, of course no school-teacher would ever tell you to do anything wrong. And now that the dance has climbed up into the social class where it is referred to politely as the ‘lingerie tremulo” that makes it seem different, too.

Morgan pointed out that it was healthful exercise, and “dancing is really cleansing to the brain and body” but “there are shimmies and shimmies, you know—nice little expurgated wriggles that are not suggestive at all—and then there is the shimmie that is decidedly vulgar. That’s why I say shimmie if you like—and according to your lights…And if you are so vulgar that you don’t know when you are doing a vulgar shimmie—why, it probably won’t hurt you any!” In the late teens to early twenties the shimmie/shimmy did occasionally get banned at dance halls, and the censors in Boston didn’t let Mae West perform it on stage in 1921,* but it looks like the fuss died down fairly quickly.

Kingsley asked Morgan about it because a shimmie dance act had been selling a lot of tickets at a rival theater, the Pantages, for the last month. Nevertheless, Morgan didn’t seem to mind giving her opinion, possibly because her act was so different. Kingsley had reviewed the ballet she’d choreographed at the Orpheum earlier in the week, and she thought it was a sensation: “it was as though I were witnessing a play—but a play done in such exquisite fashion as to be a new sort of poetry. The subject of the ballet is historical, and is in three scenes, all staged with such real and vivid appeal to the imagination the spectator feels he is in the midst of the scene itself, rather than on the outside.”

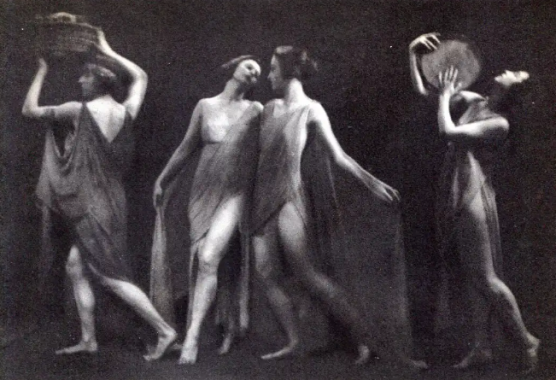

Marion Morgan was a former dance instructor who ran a troupe which toured the vaudeville circuits, performing interpretive dances based on Egyptian and classical Greek and Roman themes. She also did choreography for films. In 1927 she became director Dorothy Arzner’s partner and they worked together on several pictures.

This week there was a demonstration of just how popular Charlie Chaplin was: his new film, Sunnyside, played in two theaters at the same time, which was very unusual then. Both the Kinema (1850 seats) and Tally’s Broadway (900 seats) were owned by T.L. Tally, and according to reports, Chaplin didn’t have trouble filling all those seats. Kingsley’s review didn’t hurt; she said, “Sunnyside has so many funny touches it has to be seen to be appreciated. All lovers of Charlie Chaplin—and if there is anybody who isn’t he keeps it in the dark nowadays—will rejoice in Sunnyside.” It spent one week at both theaters, then two more just at Tally’s Broadway. Now Sunnyside is not as well regarded as many of Chaplin’s other films; however, that’s stiff competition.

Because it was a short (its run time is between 29 and 41 minutes), they felt they needed to show other films with it – even though they didn’t bother to mention them in the advertising! Here are the neglected movies: at the Kinema, they showed The Haunted Bedroom, “a good old-fashioned mystery story,” according to Motion Picture News. Meanwhile, at Tally’s Broadway during the first week they ran a Chester travelogue called Up in the Air After Alligators,** which was about alligator hunting. For the second week it was a Major Jack Allen hunting short and for the third it was The Indestructible Wife. This was a particularly odd paring; Motion Picture News called it a “matinee picture…it is one of those soft, tender kind of attraction, whose predominating feature is artistic beauty.” It told the story of a society wife (Alice Brady) who liked to go to parties, but her husband (Saxon Kling) got tired of it so he had a friend kidnap her. He rescues her so she decides to stay home. I don’t get it. I wonder how many people stuck around to watch the rest of the bill – maybe more people saw them than would have otherwise.

Kingsley had news about another big star:

That Mary Pickford is going to retire, following the completion of nine pictures for which she has contracted with the Big Four, was the statement made by Mrs. Charlotte Pickford, Mary Pickford’s mother, according to a telegraphic dispatch received last night by this department from Boston, where Mrs. Pickford is at present, attending to details connected with the showing of a Pickford play.

“Only nine more pictures and Mary will settle down to enjoy the fruits of her hard-earned savings,” is the way Mrs. Charlotte Pickford put it. “It will take a number of months to complete the present pictures contracted for and then Mary is going to settle down to enjoy life, as I have entreated her to do for a long time. The pictures to come are to be the biggest and the best ever developed by her and she has been given free leave to spend all the money she likes to make the productions successful.”

Miss Pickford herself could not be reached last night, as she was absent from home, but her manager, F.E. Benson, states, when informed regarding Mrs. Pickford’s statement:

“I do not know of any such idea on Miss Pickford’s part. We are in the middle of a production and have a large number of stories already purchased. Of course, I don’t know what understanding Miss Pickford and her mother have regarding Miss Pickford’s retiring, but I am her manager, and I have heard no such talk.”

Of course Pickford was nowhere near retirement – that didn’t happen until 1933. It seems odd that Charlotte Pickford felt the need to alert the media about it. It could be that she though Mary really meant it. Regarding this year, Mary Pickford’s biographer Eileen Whitfield quoted the Chicago News: “Mary Pickford’s threatened retirement from professional life is becoming as chronic as Sarah Bernhardt’s farewell stage appearances.” Whitfield said that she talked about quitting because she was miserable, trying to decide if she should divorce Owen Moore and marry Douglas Fairbanks and she was quite worried about bad publicity if she did. Eventually she made up her mind, got her divorce in February 1920 and married Fairbanks a month later (and stopped threatening retirement).

Finally, this was the week when Prohibition went into effect and it was on everybody’s mind. Tom Mix said, “just think of all the family skeletons nowadays that will be moved out of closets to make room for that which cheers and also inebriates!”

*”Whirl of the Town,” Variety, April 22, 1921.

**The intertitles for the Chester travelogues were written by Katharine Hilliker, and her forgotten career is exactly what the Women Film Pioneers website was made for. She continued to work as a title writer and film editor on movies like Seventh Heaven (1927) and Sunrise (1927).